With Big Eyes, director Tim Burton refreshingly returns to more intimate filmmaking and away from the fantasy-enhanced world of his recent movies. Films like Alice In Wonderland (2011) and Dark Shadows (2012) were so concerned with heightening their fantastical premises, performances were lost in special effects and makeup and took a backseat to art direction and production design. The animated Frankenweenie (2012) was wonderful, but it was an extension of a story he first shot as a short in 1984. Burton’s early concern for championing the outsider while sprinkling the film’s narrative with a morbid humor is what made such early films like Beetlejuice (1988), Edward Scissorhands (1990) and even his reinterpretation of Batman (1989, 1992) so special. But as story grew more outlandish, characters seemed to grow more hollow and less engaging. Burton’s film just grew dull in their kaleidoscopic exuberance.

With Big Eyes, director Tim Burton refreshingly returns to more intimate filmmaking and away from the fantasy-enhanced world of his recent movies. Films like Alice In Wonderland (2011) and Dark Shadows (2012) were so concerned with heightening their fantastical premises, performances were lost in special effects and makeup and took a backseat to art direction and production design. The animated Frankenweenie (2012) was wonderful, but it was an extension of a story he first shot as a short in 1984. Burton’s early concern for championing the outsider while sprinkling the film’s narrative with a morbid humor is what made such early films like Beetlejuice (1988), Edward Scissorhands (1990) and even his reinterpretation of Batman (1989, 1992) so special. But as story grew more outlandish, characters seemed to grow more hollow and less engaging. Burton’s film just grew dull in their kaleidoscopic exuberance.

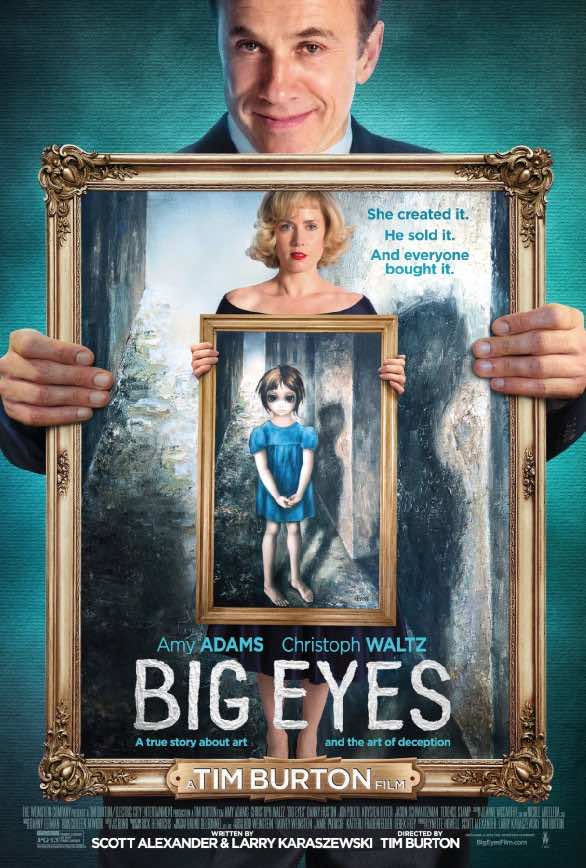

With Big Eyes, the Tim Burton who really loves people and their faults is allowed to shine in a film not weighed down by concept and fantasy. The film follows the true-life story of a painter whose images of children with gigantic eyes became so much bigger than their creator in 1950s popular culture that her husband was able to take credit for her work. As much as they are credited for producing an iconic image of the era, Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz) and Margaret Keane (Amy Adams) were also a product of the 1950s, and the film’s drama is very much informed by the culture that celebrated man as the bread-winner and the woman the house-bound, kept person. As the film’s narrator, reporter Dick Nolan (Danny Huston), says, “The ‘50s were a wonderful time if you were a man.”

Key to a sense of renewal for Burton is the script by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who have not worked with Burton since this writer’s favorite Burton movie Ed Wood (1994). Once again they have brought to life passionate souls primed for the cinema of Burton. Newly divorced Margaret harnesses the power of art as her only avenue of unencumbered expression. Meanwhile, free-spirited Walter grows so obsessed with co-opting her power, he will sacrifice his eventual marriage to Margaret to maintain the façade that he is the author of her work.

They meet at an art fair in San Francisco (his booth of Paris street scenes is next to hers). “You’re better than spare change” he tells her when she compromises her price from one dollar to 50 cents for a man negotiating the price of a portrait of his son. Walter flirts and flatters her, immediately appearing like a smooth-talking con man, scheming his way into  her life. Even though her daughter Jane (Delaney Raye) is ever suspicious of Walter, the tired and worn out Margaret is easy prey for his charms. They marry quick, even though from the start he sees art very differently than she does. When the meet, he immediately questions her paintings as having “out of proportion” eyes. He describes her subjects as having “big, crazy eyes … like pancakes.”

her life. Even though her daughter Jane (Delaney Raye) is ever suspicious of Walter, the tired and worn out Margaret is easy prey for his charms. They marry quick, even though from the start he sees art very differently than she does. When the meet, he immediately questions her paintings as having “out of proportion” eyes. He describes her subjects as having “big, crazy eyes … like pancakes.”

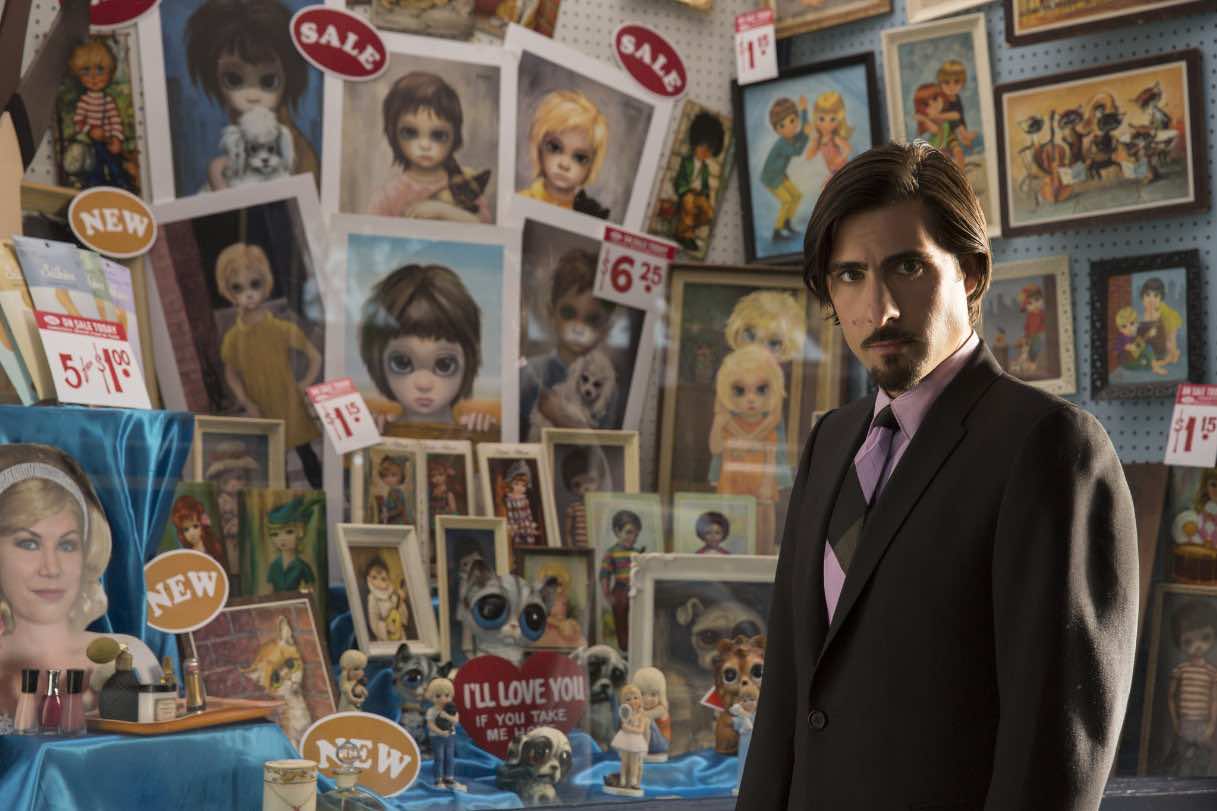

The script does not ever elevate the art to anything beyond kitsch. Dick calls the subjects “weird hobo kids.” It both isolates Margaret and adds a layer of critique of the era. However, Margaret, a woman desperate to express herself with her art, no matter what others think, still comes across as incredibly sympathetic. Even though an art dealer (Jason Schwartzman) refuses to sell her paintings and is  flummoxed when Walter opens a gallery across the street that has lines of people waiting to go inside, Margaret remains steadfast in her pure, honest need to paint these images. “All I ever wanted was to express myself as an artist,” she says, hanging on to the words for dear life. “These children are a part of my being.” Walter, in the meantime, finds a way to mass produce the images and sell them in supermarkets, perplexed by her words. “I’m a businessman,” he counters in his defense for presenting the work as his own creation. “Sadly, people don’t buy lady art,” he explains.

flummoxed when Walter opens a gallery across the street that has lines of people waiting to go inside, Margaret remains steadfast in her pure, honest need to paint these images. “All I ever wanted was to express myself as an artist,” she says, hanging on to the words for dear life. “These children are a part of my being.” Walter, in the meantime, finds a way to mass produce the images and sell them in supermarkets, perplexed by her words. “I’m a businessman,” he counters in his defense for presenting the work as his own creation. “Sadly, people don’t buy lady art,” he explains.

Then there are the performances. Adams does amazing work in a role that asks her to contain herself. She barely speaks, but when she does, her speech is steeped in an expression of repressed emotions with a need to be heard. Reflective of Margaret’s paintings, Adams plays much of her role with her eyes. Waltz plays Walter with a balance of passion for his lies that conflicts with a woman who he thought he married as a kindred spirit. But it’s not on her, it’s on him. As the film comes to reveal he has lied his own sense of being into existence. He’s more than some flimflammer, he’s a man who has corrupted his own sense of self and has dug himself so deep in his own delusions that he can’t find a way out. Waltz plays Walter with an urgent energy of repressed self-doubt that still comes across as sympathetic and not just smarmy. It builds toward a sad denouement, where Walter practically imprisons Margaret in the mansion they built on commercializing her art and a bizarre courtroom battle based on actual transcripts from a slander suit where Walter acts as his own attorney.

Burton’s style is certainly not lost in all this. The humor comes from pathos and is never ironic. The director’s heightened, graphic style of representing the era is vivid and captivating with the help of production designer Rick Heinrichs and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel. Early in the film, the road out of the suburbs that Margaret has escaped recalls the simplified, high contrast landscapes of her paintings. When the Keanes honeymoon in Hawaii, the beaches and hotels look like something out of a postcard from the era.

Big Eyes gives us a refreshingly subdued Burton that does not betray his characteristic style of movie making. It also features a subject he finds no trouble investing in, and his own passion for cinema shines through. If it ever over-reaches its sense of realism, it’s only to inform the passions driving these people in the way only Burton can do it, so it feels easy to both forgive and relish. The film comes from a heartfelt place in direction, writing and performance, and it goes to show Burton is still deeper than superficial style.

Big Eyes runs 105 minutes and is rated PG-13. It opens in South Florida at O Cinema – Wynwood on Dec. 25. It’s also being released at pretty much every multiplex across the U.S., but don’t forget to support indie cinema. We caught this film at a free advance screening during Art Basel – Miami Beach.

A return to Burton’s roots by the sound of things- sounds like a great watch! When is due to hit cinemas in the UK?

Hi! Thanks for reading my review. It came out on Dec. 26th in the UK, so it should already be playing there.