As already established in my earlier posts culled from several interviews with Mike Garson for an unpublished piece regarding his contribution to the music of David Bowie from 1972-2006 (Mike Garson talks about ‘David Bowie Variations’: an Indie Ethos exclusive, From the Archives: Mike Garson on working with David Bowie (Part 1), From the Archives: Mike Garson on working with David Bowie, the later years (Part 2)), Garson brought a colorful experience in jazz when Bowie called on him to join the Ziggy Stardust tour. Garson had no experience in rock and no idea who this David Bowie character– with his orange mullet and glitter makeup– was. So how did a classically trained jazz man like Garson wind up being Bowie’s most consistent side man of his career?

As already established in my earlier posts culled from several interviews with Mike Garson for an unpublished piece regarding his contribution to the music of David Bowie from 1972-2006 (Mike Garson talks about ‘David Bowie Variations’: an Indie Ethos exclusive, From the Archives: Mike Garson on working with David Bowie (Part 1), From the Archives: Mike Garson on working with David Bowie, the later years (Part 2)), Garson brought a colorful experience in jazz when Bowie called on him to join the Ziggy Stardust tour. Garson had no experience in rock and no idea who this David Bowie character– with his orange mullet and glitter makeup– was. So how did a classically trained jazz man like Garson wind up being Bowie’s most consistent side man of his career?

During my first interview with Garson, when I met him in 2004, I began our conversation with some questions about his jazz experience, which would eventually lead him to working with Bowie.

I met him backstage, in a small, isolated dressing room at the James L. Knight Center in Miami, just hours before Bowie and his band was supposed to take the stage on May 4, during the Reality Tour’s stop in Miami. He was sitting in front of a Yamaha Motif, preparing to warm up for the show, as was his regular routine while on tour with David Bowie.

Our conversation that day wound up mostly focusing on his experience in jazz, before going deeper into his approach to the piano. He would illustrate a lot of his points on the keyboard, some samples of which I have converted into mp3 files posted throughout the rest of this interview, which will continue in two more parts.

Our conversation that day wound up mostly focusing on his experience in jazz, before going deeper into his approach to the piano. He would illustrate a lot of his points on the keyboard, some samples of which I have converted into mp3 files posted throughout the rest of this interview, which will continue in two more parts.

On with the interview, which I had hoped to convert into a more feature-oriented piece that never came to be, as detailed in the earlier posts about Garson already posted on this blog. Please note that you will find I ask a lot of questions about his age and what time whatever happened. It would have been what feature writers call “color,” not necessarily direct quotes. But since the story never happened, here is part 1 of that full conversation:

Hans Morgenstern: One of the first things I saw in my research is that you once had a six-hour session with Bill Evans. Is that true?

Mike Garson: Well, yeah. When I grew up on the New York jazz scene in the sixties, I sort of wanted to take advantage of all the great jazz pianists around.  I was a gigantic Bill Evans fan. I used to sit this close to him at the Village Vanguard, watching him play and watching his hands. I used to steal my father’s car out of the house, from Brooklyn— I was 16— and just drive down to the Village Vanguard in Manhattan and just watch him play all night. I would get this corner table, and I could see the piano perfectly, so, one day, I got the nerve, a year or two later, to say, “Can I have a piano lesson?”

I was a gigantic Bill Evans fan. I used to sit this close to him at the Village Vanguard, watching him play and watching his hands. I used to steal my father’s car out of the house, from Brooklyn— I was 16— and just drive down to the Village Vanguard in Manhattan and just watch him play all night. I would get this corner table, and I could see the piano perfectly, so, one day, I got the nerve, a year or two later, to say, “Can I have a piano lesson?”

He said, “Yeah,” and I went up to his place. He spent six hours with me. He didn’t charge me a penny, and we went over some tunes, jazz things, and he showed me how he harmonizes them and voices them, so he would show me different chord substitutions for tunes. He used to carry around a little notebook when he would be on the train, going to gigs, and if he heard a little idea in his head, he would sketch it out, so he kind of showed me a little bit how his creative process worked.

Plus, we shared something in common. He liked Lennie Tristano, and I don’t know if you know Lennie Tristano. Lennie Tristano was a blind pianist. He was phenomenal, actually. A real unsung hero. He’s not alive anymore. I studied with him for three years. Lennie Tristano played with Charlie Parker. He had his own school of music.

This was after your meeting with Bill Evans?

I was studying with him [Tristano] at the time. I had already had two years with Lennie Tristano, so I was just adding Bill in as an additional little supplement because I knew it was just going to be one lesson with him. With Lennie it was weekly. Lennie taught people like Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh, they were sax players. Lee Konitz is still alive. Warne Marsh is not. He had a whole little school of people who played jazz in his style—very advanced harmonic concept and rhythmical concept. The Tristano School was almost like a cult in New York in the fifties and the sixties and the seventies, so I had the luck to study with him for three years. There’s a little playing of Bill Evans on an album that Bill did called New [Jazz] Conceptions in 1956 and there’s a couple of tunes on there where you could see that Bill Evans got influenced by Lennie Tristano, so we got talking about that.

I was studying with him [Tristano] at the time. I had already had two years with Lennie Tristano, so I was just adding Bill in as an additional little supplement because I knew it was just going to be one lesson with him. With Lennie it was weekly. Lennie taught people like Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh, they were sax players. Lee Konitz is still alive. Warne Marsh is not. He had a whole little school of people who played jazz in his style—very advanced harmonic concept and rhythmical concept. The Tristano School was almost like a cult in New York in the fifties and the sixties and the seventies, so I had the luck to study with him for three years. There’s a little playing of Bill Evans on an album that Bill did called New [Jazz] Conceptions in 1956 and there’s a couple of tunes on there where you could see that Bill Evans got influenced by Lennie Tristano, so we got talking about that.

You must have been really young.

You know … I was studying classical primarily, but my jazz studies were all between 15 and 20 or something. I had three lessons with Herbie Hancock. I studied with a guy named Hall Overton (Check out a great radio piece by NPR about Overton as teacher and jazz man). He did the big band charts for the Thelonious Monk albums that have big band on them, if you heard any of those albums they’re hard to find, and those are his arrangements, so I got to study with him.

I remember reading Thelonious Monk did big band, but I never heard any of those records.

He had a big band for a little period of time, and this guy, Hall Overton, was my teacher for two years. He did those arrangements, and, right after my lesson, Tony Williams used to take a composition lesson with Hall Overton. I mean, what I’m trying to say from all this, since you brought up Bill Evans, is I was able to be a sponge and be right on that New York scene. I mean, I got to work with Elvin Jones, who was [John] Coltrane’s drummer.

He had a big band for a little period of time, and this guy, Hall Overton, was my teacher for two years. He did those arrangements, and, right after my lesson, Tony Williams used to take a composition lesson with Hall Overton. I mean, what I’m trying to say from all this, since you brought up Bill Evans, is I was able to be a sponge and be right on that New York scene. I mean, I got to work with Elvin Jones, who was [John] Coltrane’s drummer.

Oh yeah, A friend of mind told me you played with Elvin Jones, and he wanted me to ask you about him.

Well, what happened was I went to this club to see Elvin Jones, but the piano player fell off the stand drunk [NOTE: must have been between 1971-73, when Steve Grossman was in the band, according to Allmusic.com]. They dragged him out into the street. It was on Spring and Hudson, in Manhattan, and Elvin says, “Does anyone know how to play piano in the house?” And the sax player was a guy named Steve Grossman, who I had been playing with on jam sessions. He was a very talented guy, very young, and he said, “This guy plays,” and I was like in a tuxedo. I had just come from a gig of some sort, you know, some sort of a wedding or party or something like that.

And how old were you?

How old was I then? Maybe, uh, 20, 19 or 20. And, so he points to me and Elvin sees me, and he kind of says, “Come on up, Arthur Rubinstein” because Arthur Rubinstein was a great classical pianist at that time, and he could sense, just by looking at me, that I had a classical background. These guys are very intuitive. And I went up and played a few nights with him just based on the fact that this guy fell off the bandstand drunk, and it was a great experience because I was young, and there wasn’t a more favorite drummer I preferred, even though it was a very short stint, working with him. But I also worked with Pete La Roca at that time, who was also a jazz drummer. I worked with him with Dave Liebman, the sax player. You ever hear of him? Dave Liebman?

How old was I then? Maybe, uh, 20, 19 or 20. And, so he points to me and Elvin sees me, and he kind of says, “Come on up, Arthur Rubinstein” because Arthur Rubinstein was a great classical pianist at that time, and he could sense, just by looking at me, that I had a classical background. These guys are very intuitive. And I went up and played a few nights with him just based on the fact that this guy fell off the bandstand drunk, and it was a great experience because I was young, and there wasn’t a more favorite drummer I preferred, even though it was a very short stint, working with him. But I also worked with Pete La Roca at that time, who was also a jazz drummer. I worked with him with Dave Liebman, the sax player. You ever hear of him? Dave Liebman?

Yes.

We grew up together.

Didn’t you record something with him?

Yeah, we did some recording together, too. We haven’t released the last thing we did. We did a duet, which is really interesting.

I haven’t released it yet, but we played in the Catskills Mountains together for like three or four years every summer (We went to the same high school.  I was a year older than him), but we worked with this great drummer named Pete La Roca, who’s a great drummer and Bob Moses played drums with us in that band and then Randy Brecker … There was a loft that Dave [Liebman] lived in, in New York City. There was all these great musicians. We’d have sessions. One day Mike Brecker comes in and starts playing, next day it’s Lenny White, and this is all when I’m 18, 19, 20. It’s not like that anymore.

I was a year older than him), but we worked with this great drummer named Pete La Roca, who’s a great drummer and Bob Moses played drums with us in that band and then Randy Brecker … There was a loft that Dave [Liebman] lived in, in New York City. There was all these great musicians. We’d have sessions. One day Mike Brecker comes in and starts playing, next day it’s Lenny White, and this is all when I’m 18, 19, 20. It’s not like that anymore.

That was like during the end of the hard bop era, right?

It was sort of right after that a little bit, but we were playing that style. We were a little younger than those people who were the generation before us. So we played some free music, we played some Coltrane-type music. I was playing like McCoy Tynre at the time. It was crazy stuff. It was a great time for music, and I would practice eight hours a day. In fact, about six months before the Bowie gig, I got called to work with Freddie Hubbard. I turned it down coz I was scared I wasn’t ready. Joe Henderson called. I was scared to do that, and then three, four, five years later, I heard the people that played on those records, and I was actually playing that way, but I didn’t have enough self-confidence.

But then you did work with Hubbard.

It turned out I did work with Freddie Hubbard in 1988, many years  later, and the night I got called for the Bowie gig was one night after I played a jazz club in Manhattan, on 69th Street and Broadway.

later, and the night I got called for the Bowie gig was one night after I played a jazz club in Manhattan, on 69th Street and Broadway.

This was like in ’72?

’72, and there was like three people in the club. I was playing with Dave Liebman and Pete La Roca and Steve Swallow and making $5, and I said something’s wrong with this picture, and I said maybe I should go out with a rock band, and then the next night Bowie called. But interestingly enough, the same night Woody Herman called and Bill Chase. Bill Chase, they die in a plane accident [in 1974], so it was good I didn’t do that gig. He was a trumpet player with Woody Herman, and he had his own band. Woody Herman’s gig paid very little money, and I’d played a lot of big band music already, coz I was in the Army Band for three years, so I had played in a big band, so I wasn’t excited about that, but the David Bowie gig sounded interesting, but I have to admit, I didn’t know who he was.

Well, how did he hear about you?

I had just played on an album as a session player for a singer named Annette Peacock, who had been married to Gary Peacock, who was a bass player. She was also married to Paul Bley, who’s a jazz pianist, and she knew David [then labelmates on RCA], and I had just played on her album [called I’m the One (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon)], and he respected her, and he came to America for his first tour and he said he was looking for a pianist to be on the American tour with the Spiders From Mars, and she said, “I just heard this guy who has classical and jazz background, and he might be interesting on your music.” She didn’t really tell him I was a rock player, coz I really wasn’t.

I had just played on an album as a session player for a singer named Annette Peacock, who had been married to Gary Peacock, who was a bass player. She was also married to Paul Bley, who’s a jazz pianist, and she knew David [then labelmates on RCA], and I had just played on her album [called I’m the One (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon)], and he respected her, and he came to America for his first tour and he said he was looking for a pianist to be on the American tour with the Spiders From Mars, and she said, “I just heard this guy who has classical and jazz background, and he might be interesting on your music.” She didn’t really tell him I was a rock player, coz I really wasn’t.

Stream the two songs featuring Garson’s piano on I’m the One below:

From what I’ve read and heard, I sense that you’ve taken piano playing to another level. Does this kind of playing come from wisdom or just playing for many years?

The thing is, I’m obsessed … with the piano. Some people, they orchestrate, they conduct, they played four instruments, they play drums, they play guitar, they play bass, they sing, they write harmony parts. I don’t do any of that. My whole life has been dedicated to the piano, and it’s on-going. So, I’ve looked at so much music and listened to so much music and sight-read so much music, and, personally I’ve composed like 4,000 pieces, of which half are classical.

When I was in Brooklyn College, going to school, I used to bring home music from the New York Public Library. It was the Lincoln Center Library. I’d bring home stacks and put them in the trunk of my car, and they’d let you keep it for two weeks. Then I’d bring it back, return it, bring this much back again. I used to carry it like this, walking through the streets, and I would just sight-read them. I’d only play the pieces once, so I would sight-read composers like Messiaen and Legeti and Bartók and Hindemith and Noles, Liszt and Chopin and Bach and Mozart and Godowsky and Busoni, and I would just read them like people read books, and I’d only just play them once just to absorb it. I was practicing my sight-reading abilities, but of course I was also absorbing music.

What age were you then?

It was between 21 and 25, maybe started even younger. So what I’m saying is I’ve just submerged myself in music. I wasn’t just a jazz pianist or just a classical pianist or someone who played pop or rock or casual gigs or club dates. I just did it all. Whatever came my way. I liked Vladamir Horowitz.  I like Arthur Rubenstein. I like Glenn Gould. But I loved Keith Jarrett. I loved Bill Evans. I loved Wynton Kelly. I loved Art Tatum. I loved Oscar Peterson, Bud Powell. So I was submerged in the jazz world, submerged in the classical world, submerged in what the composers wrote. I was writing my own music, and I even like commercial pianists like Roger Williams and Peter Nero and Ramsey Lewis. In other words, I had a specific love for the piano, both playing and composition. Like Chopin, for example, wrote mostly piano music. He only wrote like one concerto and a couple of orchestra pieces, but unlike Wagner or Beethoven, who wrote tons of pieces for orchestra, Chopin wrote for the piano. I’m very much like that. I have 2,000 classical pieces that I’ve written, sonatas and nocturnes and all kinds of pieces.

I like Arthur Rubenstein. I like Glenn Gould. But I loved Keith Jarrett. I loved Bill Evans. I loved Wynton Kelly. I loved Art Tatum. I loved Oscar Peterson, Bud Powell. So I was submerged in the jazz world, submerged in the classical world, submerged in what the composers wrote. I was writing my own music, and I even like commercial pianists like Roger Williams and Peter Nero and Ramsey Lewis. In other words, I had a specific love for the piano, both playing and composition. Like Chopin, for example, wrote mostly piano music. He only wrote like one concerto and a couple of orchestra pieces, but unlike Wagner or Beethoven, who wrote tons of pieces for orchestra, Chopin wrote for the piano. I’m very much like that. I have 2,000 classical pieces that I’ve written, sonatas and nocturnes and all kinds of pieces.

I’ve heard little bits of them on your website.

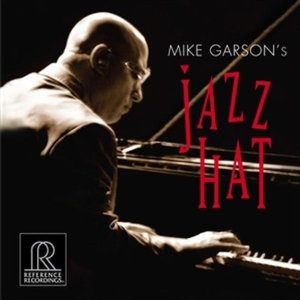

Yeah, there’s some things on there. I’ll give you a record. I stuffed one in my suitcase. It’s not out yet, it’s called Homage to my Heroes (Support the Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon).

Those are the clips that I heard

But there was some earlier versions. This is a new one. There’s two volumes.

So, if I’m understanding this right, this is basically some of the musicians you mentioned, and you’ve taken their style and done it your own particular way?

Not even that. It’s more like they inspired me at a certain point in my life, whether it was for one day or for a month or for a year. When I wrote the piece I might have just been thinking about them. They all really sound like me and very seldom someone would say that sounds like Messiaen or Bach or this and that.  Once in a while it’s obvious. They’re me, but it’s more that they inspired the music, as opposed to copying, but the whole concept behind the album. See, I was trying to figure out what type of legacy could I leave in music that would be different from Leonard Bernstein or Gershwin or Beethoven or Bach or Chopin because they all wrote music this way, by hand, so they composed the pieces, but I had spent 30 or 40 years improvising, so I started writing classical pieces as improvs, but into my Yamaha Disklavier player piano, so it would record all the data and then I’d give the MIDI files to this guy who works with me, and he prints out the music. Something that might have taken me three weeks I’ve done in one shot. I would play on a regular grand piano, and it will record the data, and then they would put it in a program called Finale. It prints it out, then you have to finesse it a little bit. Then I give those pieces to concert pianists, and they play them. I never have played these 2,000 pieces. I just improvise them once, so they might sound like this…

Once in a while it’s obvious. They’re me, but it’s more that they inspired the music, as opposed to copying, but the whole concept behind the album. See, I was trying to figure out what type of legacy could I leave in music that would be different from Leonard Bernstein or Gershwin or Beethoven or Bach or Chopin because they all wrote music this way, by hand, so they composed the pieces, but I had spent 30 or 40 years improvising, so I started writing classical pieces as improvs, but into my Yamaha Disklavier player piano, so it would record all the data and then I’d give the MIDI files to this guy who works with me, and he prints out the music. Something that might have taken me three weeks I’ve done in one shot. I would play on a regular grand piano, and it will record the data, and then they would put it in a program called Finale. It prints it out, then you have to finesse it a little bit. Then I give those pieces to concert pianists, and they play them. I never have played these 2,000 pieces. I just improvise them once, so they might sound like this…

Listen to Gason’s demonstration

… so my whole concept behind music is if you can capture how you feel at any given second, you are being totally true to yourself and the music but very seldom do I get a chance to create like that. When you’re in a band, you have to play parts. Now, with David, I get more improvisation time than any of the other members because I’m sort of sitting on top of the guitars and bass and drums, so I’m like the whip cream on the cake. So I can improvise a little more, but I still have to play some parts exact.

* * *

In part 4 of this ongoing interview series, I went a little deeper with Garson into what exactly he might be thinking when he plays the way he does.

I’ll leave you with a YouTube video Mike shared of one of his more recent jazz performances (no embed allowed so copy and paste):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d4lleuH7Ku4&

This is continued from Part 2: From the Archives: Mike Garson on working with David Bowie, the later years (Part 2 of 5)

This archival interview series continues here: From the Archives: Mike Garson on playing the piano (Part 4 of 5)

Reblogged this on celestedancer and commented:

Part 3 of 5 of a wonderful series of articles on Mike Garson – From jazz to Bowie