Anyone who recalls the early nineties dance club era featuring chill rooms, breakbeats and jungle music, before EDM started to drive today’s bass-dropping, dub-stepping electronica and PLUR culture, understands the sudden tectonic shifts of the ever fluid scene of dance music. The scene feels so capricious that even referencing PLUR, much less dub-step, already feels dated. Though I’ve written about music for over 20 years and can say I saw Orbital play a nightclub in Miami Beach, I can’t relate to anything at the long-surviving Ultra Music Festival that my city is so well known for. It’s a whole other world now. It’s no wonder few DJs and electronic music acts have survived the gauntlet of time (again, see Orbital). They could either evolve, become nostalgia acts or worse, disappear into irrelevance.

Anyone who recalls the early nineties dance club era featuring chill rooms, breakbeats and jungle music, before EDM started to drive today’s bass-dropping, dub-stepping electronica and PLUR culture, understands the sudden tectonic shifts of the ever fluid scene of dance music. The scene feels so capricious that even referencing PLUR, much less dub-step, already feels dated. Though I’ve written about music for over 20 years and can say I saw Orbital play a nightclub in Miami Beach, I can’t relate to anything at the long-surviving Ultra Music Festival that my city is so well known for. It’s a whole other world now. It’s no wonder few DJs and electronic music acts have survived the gauntlet of time (again, see Orbital). They could either evolve, become nostalgia acts or worse, disappear into irrelevance.

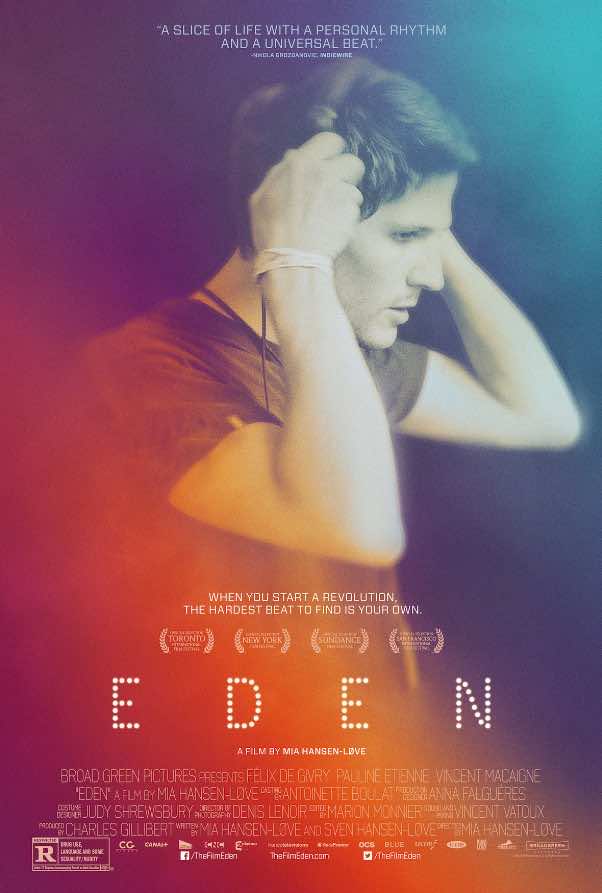

Eden, the latest film by French director Mia Hansen-Løve, chronicles the path of a fictional DJ (Félix de Givry) in early nineties Paris inspired by the music scene of the time. It follows him over the course of a decade as he earns some recognition as part of a DJ duo and struggles to stay relevant in the scene’s casual drug-fueled atmosphere. Meanwhile, a parallel story line depicts how Daft Punk weaves in and out of his life. This movie is so much more than the simple logline following it around: “Paul, a teenager in the underground scene of early nineties Paris, forms a DJ collective with his friends and together they plunge into the nightlife of sex, drugs, and endless music.”

Hansen-Løve has a marvelously unglamorous, naturalistic style. What’s amazing about this movie is how slowly the characters come into their own through a rather difficult process: the bliss of music and the disillusionment of the cycle of that music’s scene — sex and drugs is but a footnote. Few can make such a lifestyle last a lifetime, and Hansen-Løve, who wrote the script with her brother Sven Hansen-Løve, captures the futility of a young man’s attempt with a delicate, patient touch. The director finds an incredible balance that places music at the forefront, as characters are fleshed out through the more universal cauldron of time.

Hansen-Løve has a marvelously unglamorous, naturalistic style. What’s amazing about this movie is how slowly the characters come into their own through a rather difficult process: the bliss of music and the disillusionment of the cycle of that music’s scene — sex and drugs is but a footnote. Few can make such a lifestyle last a lifetime, and Hansen-Løve, who wrote the script with her brother Sven Hansen-Løve, captures the futility of a young man’s attempt with a delicate, patient touch. The director finds an incredible balance that places music at the forefront, as characters are fleshed out through the more universal cauldron of time.

We first meet Paul against the sounds of “Plastic Dreams” by Jaydee. We are told it’s November 1992. He and Cyril (Roman Kolinka) wander into the woods after a night of clubbing, high on drugs and music. Paul is inspired, a vision of an animated bird — the film’s only betrayal of realism — portends inspiration but also false hope. His companion will also become a noted cartoonist who attempts to document the Parisian dance scene in a comprehensive series of graphic novels, which will turn out to be an even greater exercise in futility, something Hansen-Løve seems astutely aware of, as the film maintains a narrative focus on Paul, but leaves Cyril as a peripheral if more tragic side note. With her focus set on Paul, Hansen-Løve never resorts to a literal tight focus. She presents the world around Paul in mostly medium shot. The rest of the world and the people that come and go and sometimes return, including several girlfriends (among them Greta Gerwig), are essential.

With Stan (Hugo Conzelmann) at his side, Paul seems on the right track toward success after forming the garage duo Cheers. They get some decent headlining gigs at clubs and earn radio appearances. Meanwhile, their friends Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo (Arnaud Azoulay) and Thomas Bangalter (Vincent Lacoste), a.k.a. Daft Punk, get a few good notices, as well. The Daft Punk duo, however, like Cyril, are presented as a couple of oddballs on the periphery, who still have a hard time getting into clubs, even at film’s end, in “modern times” and riding a wave of many moments of  success, all of which occur off-camera. But this is never presented as some kind of rivalry. Paul and Stan genuinely admire the early, French house developments of Daft Punk (which began as Darlin’ in 1992 with Phoenix’s Laurent Brancowitz on drums), and they continue to be friendly into the later years. This restraint is only part of the film’s natural unfolding. There’s no obligation to present the exact time where Paul is at in his life, though the film is presented chronologically and references to years appear, like one to 1995 in the early part of the movie. But it never feels heavy-handed. The demarcation of time is more clearly revealed in the changes of music, from recognizable tunes to the evolution of the scene’s sound, or the changes in Paul’s life, from girlfriends to his mother’s growing frustration with his obsession to make DJ-ing a career.

success, all of which occur off-camera. But this is never presented as some kind of rivalry. Paul and Stan genuinely admire the early, French house developments of Daft Punk (which began as Darlin’ in 1992 with Phoenix’s Laurent Brancowitz on drums), and they continue to be friendly into the later years. This restraint is only part of the film’s natural unfolding. There’s no obligation to present the exact time where Paul is at in his life, though the film is presented chronologically and references to years appear, like one to 1995 in the early part of the movie. But it never feels heavy-handed. The demarcation of time is more clearly revealed in the changes of music, from recognizable tunes to the evolution of the scene’s sound, or the changes in Paul’s life, from girlfriends to his mother’s growing frustration with his obsession to make DJ-ing a career.

Eden is not some survey or comprehensive account of the genre through the eyes of Parisians, however. That would prove detrimental to Paul’s story, as ironically demonstrated by the fate of Cyril. A film that would have focused too much on the music, would detract from the people in it. If that is all these people define themselves by, what else is there that matters? The film is focused on telling one man’s story and all the others’ lives are filtered through his eyes. In one scene he is rolling in bed with Julia (Gerwig), who is in  Paris on a student visa. A bit later in the story, he is catching up with her in New York City as a guest DJ at a museum rave in the daylight. At this point in our story she is married and pregnant. Paul’s journey as a person flows with the trivializing of a music genre that has to constantly adapt for relevance. This is how the world of electronic music shrewdly informs the film. Music becomes more than a sonic landscape that captures atmosphere and time changing over the course of the film. It is also presented as either a fit for our hero or a foil. The conflict is as much in his trying to fit in with the music as much as in the passive-aggressive dynamism between his girlfriends, pals and rivals.

Paris on a student visa. A bit later in the story, he is catching up with her in New York City as a guest DJ at a museum rave in the daylight. At this point in our story she is married and pregnant. Paul’s journey as a person flows with the trivializing of a music genre that has to constantly adapt for relevance. This is how the world of electronic music shrewdly informs the film. Music becomes more than a sonic landscape that captures atmosphere and time changing over the course of the film. It is also presented as either a fit for our hero or a foil. The conflict is as much in his trying to fit in with the music as much as in the passive-aggressive dynamism between his girlfriends, pals and rivals.

Eden speaks to character flaws and humanity in a warm, relatable way. If all we have is a list of hits or notable touchstones in this music scene, where is a life lived within this world? Hansen-Løve is clearly more interested in creating a feeling for a life, above all. As she did with her stellar prior film, 2011’s Goodbye First Love, she creates a profound impression of living life and enduring its inevitable life-changing conflicts and surviving them to confront new ones with an informed, unshakable past. She harnesses all the power of the language of cinema, from framing to editing to writing to acting to tell a story without calling attention to the technique. Eden just happens to also have a pretty cool, eye-opening soundtrack that works incredibly well as a narrative device.

Eden runs 131 minutes and is Rated R. It came out on home video Tuesday, Jan. 20. Support Independent Ethos, purchase on Amazon, via this link. Broad Green Pictures shared a preview link to this film last year when it almost hit theaters in Miami. It’s also on-demand on Amazon (follow this link).