All of music has lost some of its luster today. David Bowie died at the age of 69. Suddenly, the album he released, just a few days earlier, on his birthday no less, makes a little more sense.

All of music has lost some of its luster today. David Bowie died at the age of 69. Suddenly, the album he released, just a few days earlier, on his birthday no less, makes a little more sense.

“★” (pronounced “Blackstar”). It’s tempting to listen to “‘Heroes'” or “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” now, but play that album in his memory instead. It was a brilliant example of his continued vitality in music. Today it just got more vital with this new layer of resonance. It’s a twist of fate that Bowie must have foreseen considering it turned out he was battling cancer for the past 18 months. Only Bowie could have pulled this off, so kudos to him on his way out of this mortal realm. His last great trick in rock ‘n’ roll.

To repeat his achievements would be redundant, so let’s leave that to the other obit writers. Just jump through our David Bowie tag to understand how important he was to this blog (as soon as I get the vinyl, expect a review for “★” with what is now a clearer perspective than most reviews out there).

No, today this writer will share something more personal. How and why I credit my love of David Bowie’s music for kicking off my writing career.

It began in ninth grade, at a school in the Kendall suburb of Miami called Arvida Middle School. It was 1987. My English teacher, Ms. Stinson, was a wide, round-faced black woman, who was the most intimidating instructor I had in that grade. I remember that classroom being very quiet, and if there were any bullies and smart alecks in that class, they must have stayed quiet too.

One day, we were assigned books to read and then present to the class. Ms. Stinson had a list of famous names on a sheet of paper she passed out to the class, and we were to pick from the list who we wanted our presentation to be about. I sat toward the back of the final row in class, having to pick from the leftovers. I got Janusz Korczak’s book Ghetto Diary. I never heard Korczak’s name until this assignment. Needless to say, I did not feel invested in this topic. I remember struggling to get into the book, which we had to check out from our school’s library. I don’t think I ever read the entire book, just skimmed through it looking for some distinctive bits to regurgitate in class.

Some days later, when it came time to head to the front of the class to stand by Ms. Stinson’s desk, I was rattled with nerves. I had barely a notion how to pronounce my subject’s name, much less any recollection of anything I gleaned in his book. It’s a closed off memory as to what exactly happened. Maybe students laughed at my stuttered, unsure pronunciation of Janusz Korczak, maybe all I could recall from the book was when Korczak spoke with God, as he headed off to a death camp. I might have failed to answer any questions that my teacher asked after that “presentation.” It was a haze and remains so to this day. I just remember how scary Ms. Stinson seemed.

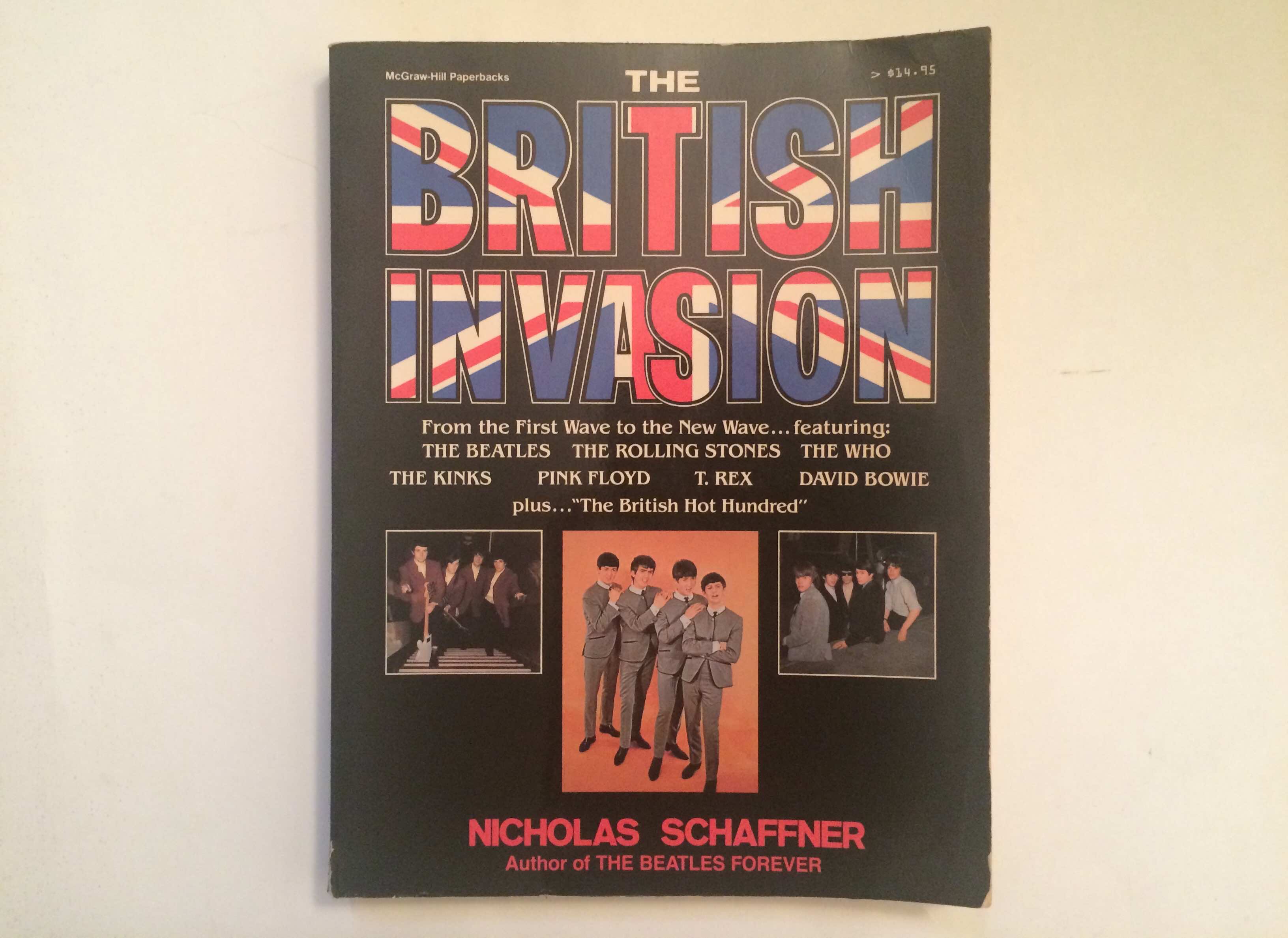

Well, she frightened up until the end of class. Sometime soon after the botched presentation, she pulled me and a few other students aside who didn’t do too well on our presentations to offer us a do-over. This time we could pick the topic. She said to bring a book into the next class featuring a person we wanted to discuss. I had been reading Nicholas Shaffner’s The British Invasion: From the First Wave to the New Wave. I still own that book:

I brought it to class the next day and showed her the section on David Bowie. “You want to do David Boowie?” she said, mispronouncing his name but with a smile. I didn’t correct her. She suggested I play some of his music to the class during my presentation. The ease I felt after playing the opening part of my cassette of Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture dissolved any stage fright. My curiosity of what Bowie did during that fateful 1973 concert where he appeared as an alter ego in bright orange hair, the brashness of his backing band, The Spiders From Mars, flowed out as I schooled my classmates on Bowie.

At that age I had a pretty clear grasp of who Bowie was and what he meant in rock ‘n’ roll history. I hardly had to cite my source. At about 15 years old, I learned I could be an authority on David Bowie, and I would later go on to review several of his releases for local music publications. Because Bowie’s music over the years was so diverse, featuring influences from Little Richard to Neu!, he opened my musical interests wide, as well.

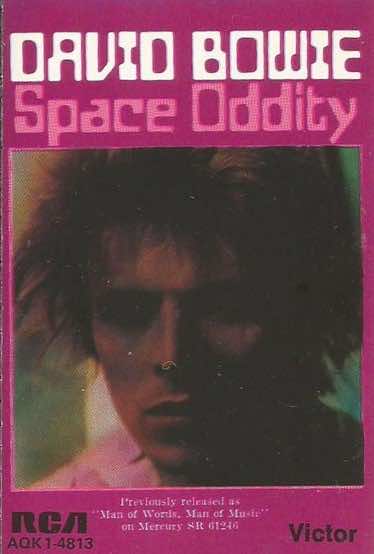

Bowie’s image, especially in the early ‘70s, played a great part in converting fans. Many speak of seeing him on the BBC show Top of the Pops doing “Starman” in a jumpsuit with that orange mullet and cozying up to his guitarist Mick Ronson. But I got into Bowie via his clean-cut Let’s Dance era via MTV, around 1984. As a young teen, I had  only cassettes and no large-form, gatefold albums to be overwhelmed by the images of him as Ziggy, which was then also used to sell earlier albums like Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World. His image, which was so important to his career then, was reduced to surreal, small, square portraits on cassette covers, which had no inner art.

only cassettes and no large-form, gatefold albums to be overwhelmed by the images of him as Ziggy, which was then also used to sell earlier albums like Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World. His image, which was so important to his career then, was reduced to surreal, small, square portraits on cassette covers, which had no inner art.

It was a strange way to get into Bowie: almost purely through his music and only his enigmatic cassette covers to guide the way (there was no YouTube back then, and I went to the library to look at music history books to find pictures of early Bowie). As I traced Bowie back through his back catalog via tapes bought at a local record shop with allowance money, I mostly latched on to the small, weird musical bits like the whooshing, oscillating intro of “Station To Station,” the strange little organ fills that gave “After All” a weird bounce, the muffled, layered, chugging guitar that hardly relented below “Joe the Lion.” I would have never sought out the music of Brian Eno, King Crimson or Faust were it not for David Bowie. I could have never appreciated the music of Bauhaus, Swans or Deerhunter without having taken apart the music of Bowie all those years earlier. He did his duty, and I will miss him till the day I die, too.