Eight years after his first film outside of either Taiwan or China (the Paris-set The Flight of the Red Balloon), Hou Hsiao-hsien could not have returned with a more Chinese film: a wuxia movie. The Assassin takes place in ninth century China, during the waning years of the Tang Dynasty. The legendary Taiwanese filmmaker, known for a meticulous style, worked with four other writers to get the details of the later years of the Tang Dynasty just right. The result is a remarkably subtle piece of storytelling that is as enthralling as it is discreet.

Eight years after his first film outside of either Taiwan or China (the Paris-set The Flight of the Red Balloon), Hou Hsiao-hsien could not have returned with a more Chinese film: a wuxia movie. The Assassin takes place in ninth century China, during the waning years of the Tang Dynasty. The legendary Taiwanese filmmaker, known for a meticulous style, worked with four other writers to get the details of the later years of the Tang Dynasty just right. The result is a remarkably subtle piece of storytelling that is as enthralling as it is discreet.

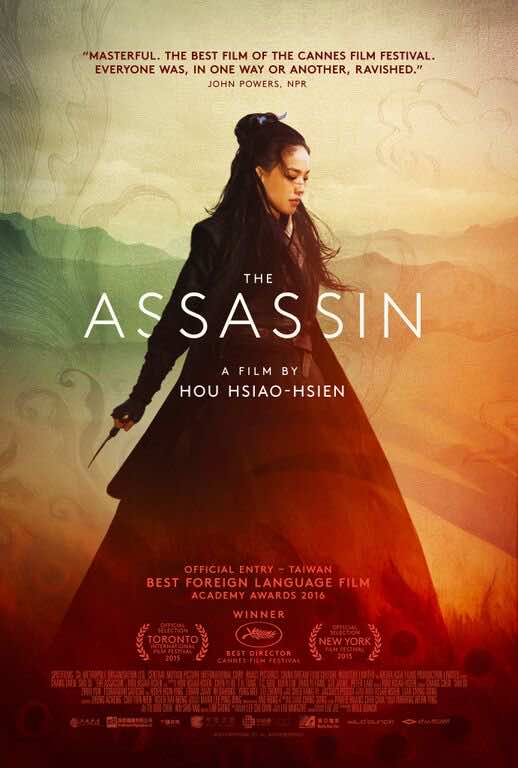

Because Hou has such a wonderful feel for location, it makes sense to describe the setting before the plot of The Assassin. He chose to shoot the film in the forests of Mongolia, standing in for ancient China. The wind creating waves over the tops of trees has as much presence as the landscape. Hou never bothers with grand exteriors of palaces where the human drama drives the story. Any appearance of a palace is obscured by trees. Even some of the fight scenes unfold behind lush branches (here’s a clip) and between tree trunks (here’s a different clip). The power of nature is also in the conflicted story of the titular assassin, Yinniang, played bracingly and with scant lines of dialogue by Hou regular Shu Qi. As often as characters talk about the past or discuss political maneuverings, nothing really matters as much as Yinniang’s quiet, conflicted feelings for her trade as a frighteningly skilled assassin.

Yinniang was abducted as a child by a former princess turned militant nun (Sheu Fang-yi) who trained her to become a killer for China’s central government. However, Yinniang has an Achilles heel: her heart. As the nun tells her, “Your skills are masterful, buy your mind is weakened by human sentiment.” After Yinniang fails one of her tasks by showing mercy, the nun sends her on a mission to kill the governor of her birthplace in Weibo Province. Lord Tian J’ian (Chang Chen) also happens to be Yinniang’s cousin. To complicate their connection, Yinniang was once betrothed to him.

Tensions run deep in this film, as many subplots course through this central arc. There’s instability in Tian’s house from politics to a strained marriage. A pregnant concubine (Nikki Hsieh Hsin-ying) becomes the target of Tian’s wife (Zhou Yun) via a deadly wizard.  Meanwhile, when Yinniang is not stalking Tian in the shadows or fighting off his guards, she finds refuge with a Japanese workman (Satoshi Tsumabuki), a mirror polisher in the countryside who she grows casually and sweetly attached to. Then there are the politics of the provinces, which seem to make the film leaden with story. However, The Assassin has a music and poetry that makes plot feel secondary. It’s reflective of Yinniang’s true path: to severe her ties with the past and begin anew.

Meanwhile, when Yinniang is not stalking Tian in the shadows or fighting off his guards, she finds refuge with a Japanese workman (Satoshi Tsumabuki), a mirror polisher in the countryside who she grows casually and sweetly attached to. Then there are the politics of the provinces, which seem to make the film leaden with story. However, The Assassin has a music and poetry that makes plot feel secondary. It’s reflective of Yinniang’s true path: to severe her ties with the past and begin anew.

The story may be complex, but it’s not hard to get beyond its complexity via Hou’s gorgeous cinema, a fluid pace of beautifully detailed mise-en-scène where the repetition of a famous Chinese poem about a blue bird and its relationship with a mirror reveals more about Yinniang than what she could ever say in dialogue. The Assassin is a cathartic thing to watch, and you will feel it deep in your soul as opposed to being told it with exposition. This is a cinema that harnesses the power of the medium by a master. Visuals, editing and sounds tell us more than words can.

Between the lavish set design, breathtaking landscapes, intricate makeup and costumes is Mark Lee’s delicate camera  work capturing shadow and flickering light to rapturous effect. From his shots of the expressively wild forests of Mongolia to the flowing silk walls during dramatic interior scenes, as the titular character lurks in the shadows, The Assassin never shortchanges the audience of impressive imagery.

work capturing shadow and flickering light to rapturous effect. From his shots of the expressively wild forests of Mongolia to the flowing silk walls during dramatic interior scenes, as the titular character lurks in the shadows, The Assassin never shortchanges the audience of impressive imagery.

Hou is known for holding unedited shots for long periods of time. His cinema is sometimes unfairly called “languorous.” To be honest, Hou’s scenes never outwear the receptive and open-minded viewer’s interest because of their rich staging. There are also moments of long monologues, and the information can feel impenetrable. It’s ironic that the film’s heroine hardly has dialogue, yet her actions and Shu’s performance speak volumes. For those hoping for lots of wuxia action, it should be noted that the film’s fight scenes are lightly sprinkled in between the drama, which eventually reveals a love story that transcends romance. Hou never takes killing lightly. You won’t see gore, guts and blood, yet he never short changes the thrills of combat. The Assassin, however, transcends its violence to reveal great compassion for humanity and life via movie-making that harnesses the power of the intrinsic medium.

The Assassin runs 107 minutes, is in Mandarin with English subtitles and is not rated (it has some violence). It opens for its premiere Miami theatrical run at the Miami Beach Cinematheque this Thursday, Oct. 29. It continues its run theatrically in Miami the following day at Tower Theater and up north in Broward County at Cinema Paradiso Hollywood. It continues to expand across the U.S. and Canada through December. For dates in other cities, visit this link. The film had its Florida premiere this past Sunday, Oct. 25, during Miami Dade College’s Miami International Film Festival’s weekend-long premieres event, GEMS. The GEMS festival hosted a preview screening for the purpose of this review, which first appeared in the Miami New Times as a shorter capsule review.

I also had an opportunity to interview Hou Hsiao-hsien, which resulted in a two-part interview below:

Hou Hsiao-hsien on his intuitive filmmaking and The Assassin; more in Miami New Times

All images courtesy of Well Go USA Entertainment.