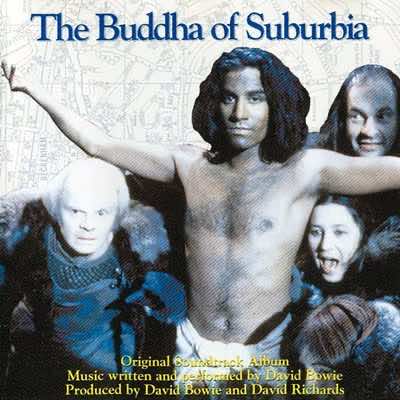

Buddha was a rapidly produced album (Bowie has said it took him six days to write and record) with the only musicians besides Bowie being multi-instrumentalist Erdal Kizilcay, pianist Mike Garson and, on one song each, Lenny Kravitz and a little known-UK group called 3D Echo. It recalled such high points as 1974’s Diamond Dogs, which saw Bowie playing most of the instruments, and 1976’s Station To Station, another quickly produced album. It also had instrumental pieces that sounded like the work he did with Brian Eno in Berlin for 1977’s Low and “Heroes.” The few songs on the album were quirky yet catchy, not unlike the songs off Low. Bowie actually reworked one of the Buddha songs, “Strangers When We Meet,” for 1. Outside, and it’s still a high point of the album.

The thing about Buddha that stands out from its bookends is how forward moving it feels without the self-consciousness of the other records. The influences of New Jack Swing in the Black Tie and industrial music for 1. Outside, not to mention this reach to bring back Eno for 1. Outside feel ham-fisted by comparison. To top it off, 1. Outside was driven by an ultra-high concept. It was supposed to be the first album of a trilogy that Bowie never completed (hence the “1.”). It also was meant as a testament to the turn of the millennium that looked back to the turn of the 20th century. When I wrote the review for 1. Outside, I happened to have been working on an independent study in college focused on late 1910s Italian Futurism, and some references in the album made an allusion to the art movement, which seemed perfect to kick off my review.

and industrial music for 1. Outside, not to mention this reach to bring back Eno for 1. Outside feel ham-fisted by comparison. To top it off, 1. Outside was driven by an ultra-high concept. It was supposed to be the first album of a trilogy that Bowie never completed (hence the “1.”). It also was meant as a testament to the turn of the millennium that looked back to the turn of the 20th century. When I wrote the review for 1. Outside, I happened to have been working on an independent study in college focused on late 1910s Italian Futurism, and some references in the album made an allusion to the art movement, which seemed perfect to kick off my review.

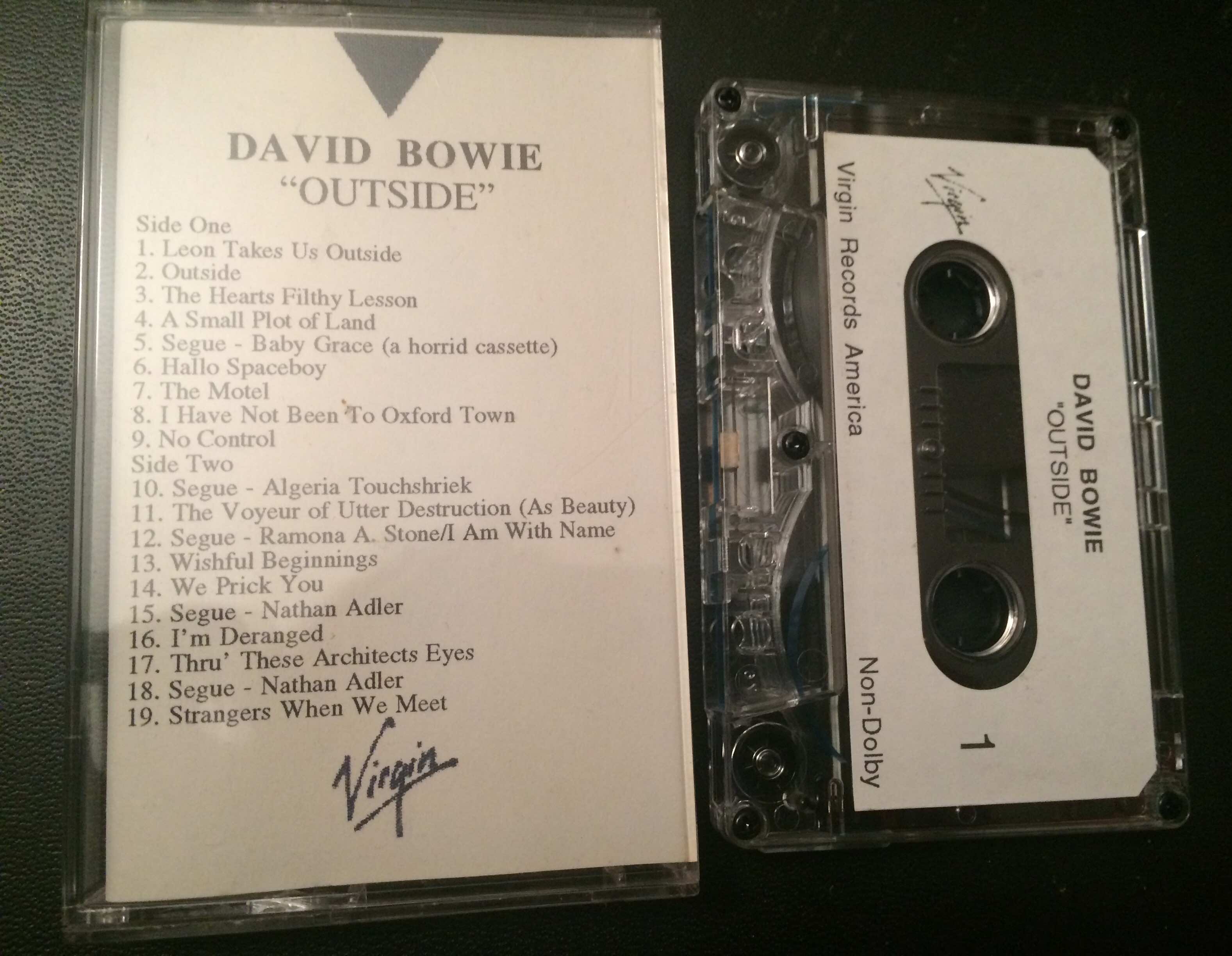

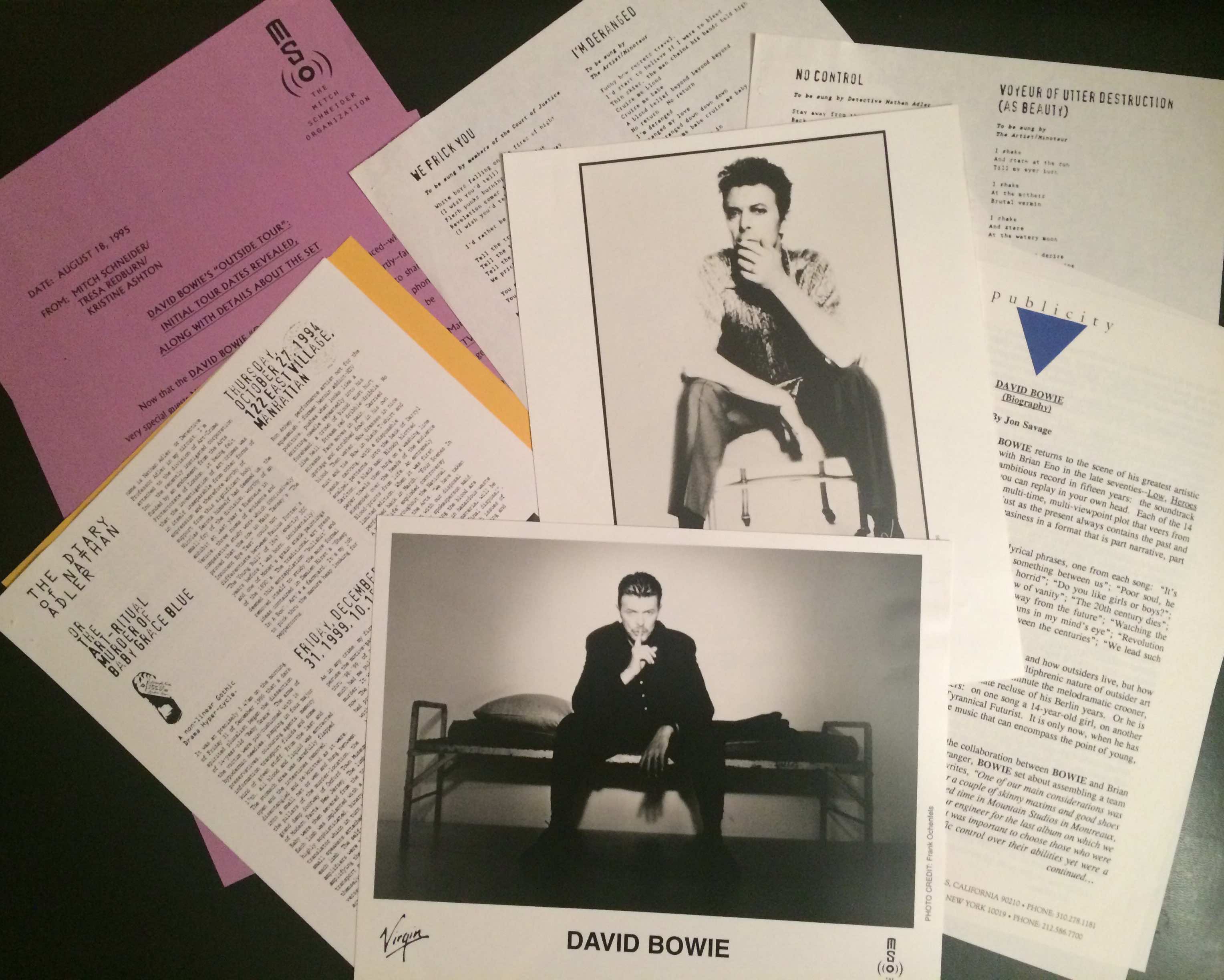

All these years later, I think it’s a better album than I originally gave it credit for. Many of the songs are counter-intuitively constructed, defying pop music conventions. They needed many repeat listens to grow accustomed to. In those days, music critics were more often than not given cassettes to review albums. I still have my copy. It was not easy to go back and forth and give particular tracks or moments closer listens with a tape, as opposed to the mp3s we get now.

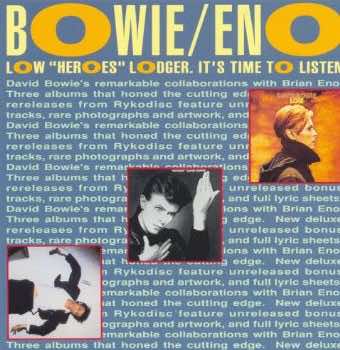

These songs are complex and the album is one of Bowie’s most conceptual works in a long time. These tracks were also created organically during jam sessions among the musicians. There was also much hype about Bowie’s reunion with Eno, who worked with Bowie and the band in the studio, even co-writing some of the songs, like he did on those important albums Bowie released in the late ’70s. Just a few years prior to 1. Outside‘s release those albums had been reissued by Rykodisc, and the hype, as always, was that Bowie collaborated with Eno on them. Eno’s name was as big as Bowie’s on the promo material (note the cover art of the promo-only CD sampler for their reissue above).

with Eno, who worked with Bowie and the band in the studio, even co-writing some of the songs, like he did on those important albums Bowie released in the late ’70s. Just a few years prior to 1. Outside‘s release those albums had been reissued by Rykodisc, and the hype, as always, was that Bowie collaborated with Eno on them. Eno’s name was as big as Bowie’s on the promo material (note the cover art of the promo-only CD sampler for their reissue above).

There are many factors that cloud our perceptions as critics. We try to absorb the art in a personal vacuum, but history, personal experience, maturity and more often slip through the filter. The fact is, I was still a college undergrad when I wrote the review below, and I feel I short-changed some credit to the genius of Bowie at the time. Though much older than when he broke barriers in the ’70s, from Ziggy Stardust to the Eno trilogy, he continued to plow new creative ground in the 1990s, and it was a challenge to absorb such an experimental and progressive album as 1. Outside after Black Tie White Noise and Buddha of Suburbia, not to mention the end of the straight-forward rock ‘n’ roll side project Tin Machine.

Below you will find my original thoughts on the album. With hindsight, I would raise the rating by a whole additional star, as I have grown to appreciate the album much more since its release.

DAVID BOWIE – OUTSIDE

Virgin: * * * (out of 5)

by HANS MORGENSTERN

Filippo Marinetti wrote the first Futurist manifesto in 1909, telling us to never look back. He preached the importance of war as a cleanser and called for the destruction of all libraries and museums. Through this campaign the futurists would allow for the creation of art in its purest form, uninhibited and uninspired by the past, an immaculate representation of the current spirit of the times.

Outside, David Bowie’s first concept album since 1974’s Diamond Dogs, explores art gone to the extreme in the not-so-distant future. It’s December 31, 1999, and self-mutilating performance art, like Chris Burden’s nude crucifixion on the top of a Volkswagen van, has become passe. In a twisted move to take shocking performance art to another level, someone has decided to dismember a 14-year-old girl and “creatively” put her body parts back together, leaving “the work” at The Museum of Modern Parts.

Outside‘s story is hard to decipher as it is the first part in a trilogy that will make up the complete diaries of Nathan Adler by 1999. All the listener really gets is the murder of Baby Grace Blue under investigation by the art-crime detective/professor Nathan Adler and a list of suspects that could include a “tyrannical” futurist suffering a mid-life crisis and the man who fell back to earth, Major Tom.

As far as the musical pacing goes, the album takes awhile to get to any outstanding tracks. The first real interesting song, both lyrically and musically, is the sixth track, “Hallo Spaceboy,” sprinkled with subtle references to Major Tom, Bowie’s subject in 1969’s “Space Oddity” and 1980’s “Ashes to Ashes.” The music, co-written by Brian Eno, deftly connotes a rocket tearing through the Earth’s atmosphere as if Major Tom might actually be plunging back to Earth. The stomping booms of Sterling Campbell’s drum kit seem to echo off electronic walls of murmuring voices from ground control as Reeves Gabrels’ angular guitar riffing melts into saxophone-like honks.

Throughout Outside the production by Bowie and Eno has a futuristic metallic shine. The opening track, “Leon Takes Us Outside,” starts with a bunch of murmurs lost in an ambient wash of noise and then bursts into “Outside,” a cut that features each instrument gleaming with its own sound. The scarcity of reverb makes each string on Bowie’s acoustic guitar ring with its own separate note.

Besides slick production, Bowie and Eno, muffle the instruments on some tracks to get a dirty, industrial sound that seems influenced by Nine Inch Nail’s Downward Spiral. “The Hearts Filthy Lesson” buzzes with NIN influences, but with Bowie’s voice mixed so high above the murmuring instruments, the song makes for a weak industrial experience.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVgk7wYeZHw

The music is at its best when its subtle and angular, coming at you with strange constructions that make for surprising listens. It makes perfect sense that Gabrels and pianist Mike Garson slip into a ska-like jam toward the end of the pounding “Hallo Spaceboy.”

Bowie and Eno worked together in the late ’70s, one of Bowie’s most prolific periods spawning the albums Low, “Heroes” and Lodger. They threw a lot of pop conventions out the window and created an avant-garde pop styling. They use this styling in Outside to reflect Bowie’s theme of art struggling to be creative. Bowie echoes the feelings toward 1920’s modernism, the parent of futurism, in lines like “There is no hell” and “We’re swimming in a sea of sham” in “The Motel.”

With Outside, Bowie sometimes falls through the trap doors of creating something new for the sake of creating something new, leaving the listener wondering if this album isn’t all a sham. One has to sit through about half an album’s worth of failed attempts at creativity that sound either like rip-offs or dull failures to get to anything ground-breaking. Overall, songs like “We Prick You” and “I Have Not Been To Oxford Town” are worth the tedium.