For his follow-up to 2012’s The Act of Killing, documentary filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer returned to Indonesia to once again explore the late 1960s massacres of innocents that put the nation’s current government in power. With The Look of Silence, once again, Oppenheimer, co-directing with the victims and the victims’ family members who he credits as “anonymous,” creates a stark testament to a grim history. As opposed to The Act of Killing where he spoke to only the perpetrators who killed people with clubs, knives and steel wire with impunity, The Look of Silence features the family members of one of the victims.

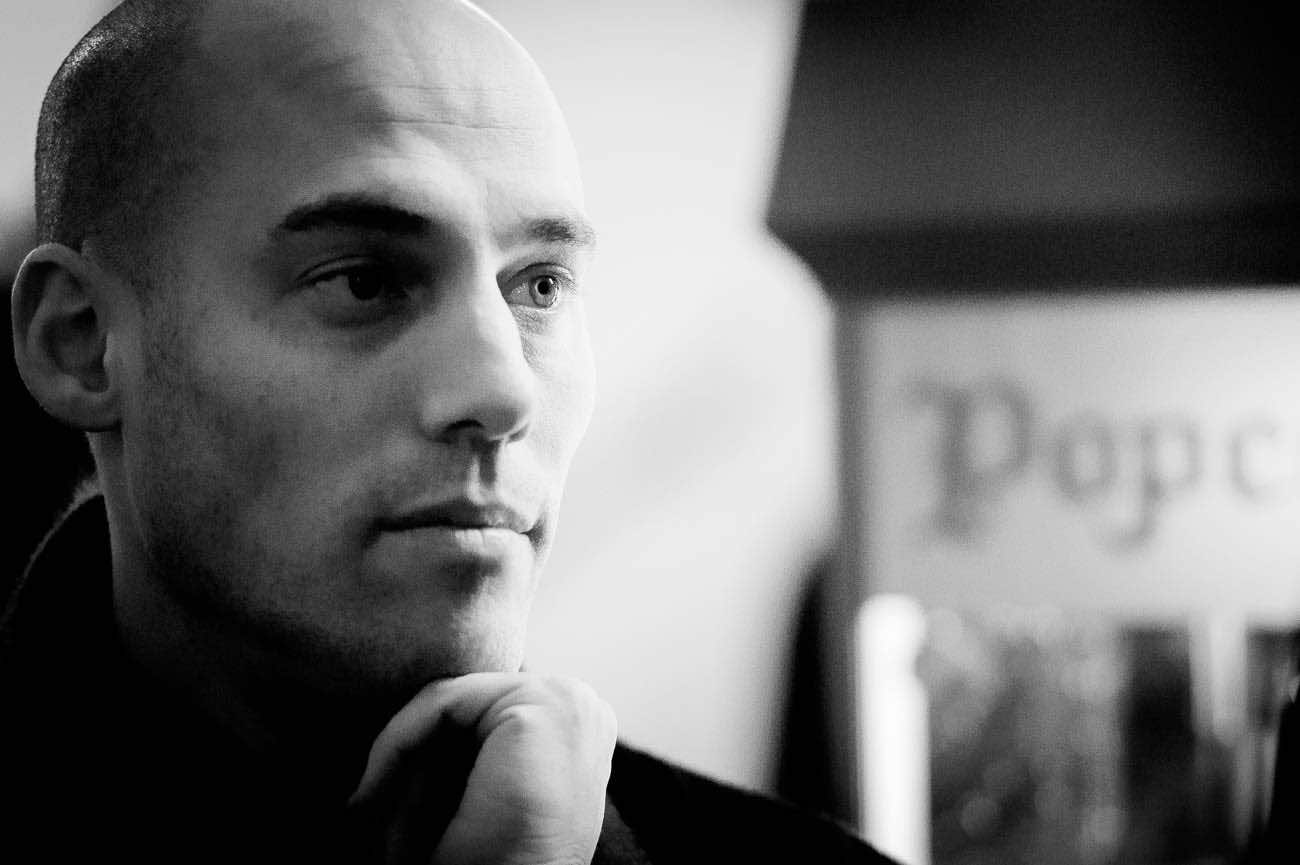

Speaking via phone from New York City, the Danish-born filmmaker reveals he first thought of this film before he shot The Act of Killing. However, he only began shooting The Look of Silence in 2012. It was actually too dangerous to identify survivors of the massacres because the current government could have imprisoned them or worse. People still live in fear of the government in Indonesia, and the release of The Act of Killing has now given him and his victims a kind of protection, though he still had to be careful not to shoot interviews with people who were too high-ranking in the government.

Oppenheimer calls The Look of Silence and The Act of Killing mirror images. He says the title The Look of Silence also came to him before The Act of Killing. Explaining the film’s title he says, “It was, above all, a definition of a project of making visible, of making palpable something normally invisible, this silence born of fear and the traces that fear and silence leave on a human life. How can you look at a family that’s lived for 50 years afraid and in silence, and in forced silence, and see the traces of that and how can you discern the inventive ways that people find to live with dignity and love, despite being surrounded by the powerful men who killed their loved ones.”

It’s a profound observation for a heavy subject. The family Oppenheimer spotlights is that of Adi, a village optician who makes the rounds testing the eyes of his neighbors, including some who actually participated in the massacre. And it is Adi who conducts the interviews with some of the perpetrators. They share with him chilling stories of drinking the blood of their victims to keep from going mad. But what mainly gets to Adi is footage Oppenheimer shot of two elderly men while making The Act of Killing. The two men stand at a clearing by the Snake River and admit they were the ones who killed Adi’s elder brother, Ramli, They even act out their actions and go into gruesome details of each machete blow that they remember. And they laugh.

The film also features Adi’s parents, his mother, who calls Adi the reincarnation of Ramli, and his father, who is now blind, toothless and suffers from dementia. In a particularly unnerving scene that Oppenheimer says Adi shot one day when he was home alone with his father, his father suffers an episode and begins crawling on the ground patting the walls crying that he doesn’t recognize where he is. “Adi explained to me, ‘I shot this because I couldn’t comfort him that day,” says Oppenheimer, “because I was a stranger to him, and I realized that it’s too late for my father to heal. He’s forgotten the son whose murder destroyed his life and his family’s life, but he hasn’t forgotten his fear, and now he’ll die like millions of others, in a prison of fear. It’s too late for him to heal because he’s forgotten what happened, and I don’t want my children to inherit this prison of fear.’”

Indeed, this is a stark movie that dwells not so much on explaining but understanding how to heal from such a past for the sake of the nation’s future. A sort of mantra is repeated by both survivors and perpetrators of the genocide: “The past is the past.” Oppenheimer explains this reasoning thus: “It’s a statement that absolutely belies itself because the survivors always say it out of fear, and the perpetrators always say it as a threat, indicating that the past is not the past. It’s right there, keeping people afraid. It’s a gaping wound. It’s an abyss dividing everybody. Keeping survivors afraid and a kind of threat by the perpetrators. The past is right there and is open … That’s really the experience of the film. I tried to create a film that’s so immersive that it goes beyond a message.”

Oppenheimer has created a poetic film, actually. It is much more than a documentary (my review: The Look of Silence explores aftermath of genocide with startling cinematic poetry). The quality of his filmmaking stands alongside the work of Errol Morris and Werner Herzog, two of contemporary cinema’s most influential and important documentary filmmakers. Both even acted as executive producers on The Look of Silence. However, Oppenheimer names very different filmmakers as influences on this film. “I kind of made a study in preparation for this use of silence of two filmmakers. I suppose for the viewing scene, I was thinking more of the work of Robert Bresson. Diary of a Country Priest, for example, the closing shot of that film, where you see a face reacting to memory and reacting to the plights of the world and the trials that are being thrown at the priest, and in the dialogue scenes, I was thinking about Yasujirô Ozu, whom I think is a master of creating dialogue scenes where everything important being said is articulated through silence and shame as opposed to the words.”

* * *

You can read much more about the film, its story and Oppenheimer’s intentions in an article I wrote for the Arts and Culture blog of “The Miami New Times.” I’m quite proud of it. Jump through the logo of the blog below to read an even more insightful piece on what is sure to be one of the greatest documentaries of the year:

Screening update: The Look of Silence returns to our Miami area thanks to the Miami Beach Cinematheque starting Friday, Sept. 4 (see screening calendar here).

The Look of Silence opens in our South Florida area exclusively at O Cinema Miami Shores on Friday, Aug.14. It plays only for the weekend. If you live outside of Miami, visit this link for other screening dates and locations. Drafthouse Pictures provided a screening link for the purpose of this review and also provided all images in this article.