“The younger generation — it means retribution, you see. It comes, as if under a new banner, heralding the turn of fortune.”

“The younger generation — it means retribution, you see. It comes, as if under a new banner, heralding the turn of fortune.”

—Henrik Ibsen, The Master Builder

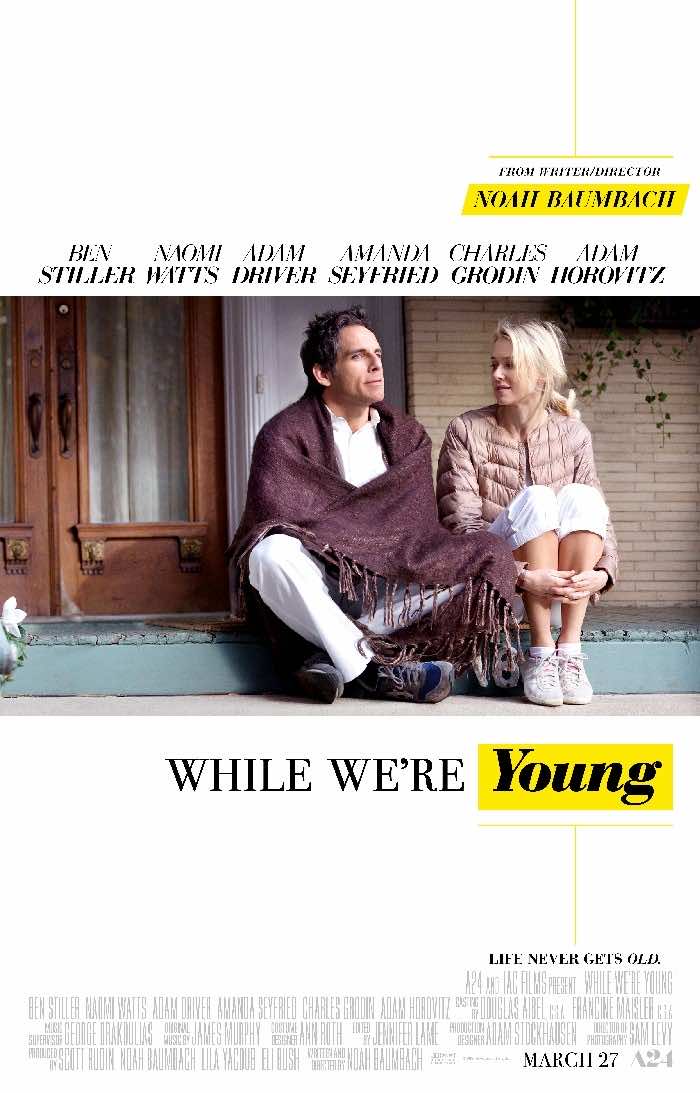

I don’t believe that was one of a series of too many quotes that popped up on a black background in silence at the start of While We’re Young, but it probably best represents the sense of dread the film was trying to capitalize on. In a society that has become so post-cultural and progressive, it gets a little hard to get old, and no one seems more obsessed with transmitting that than writer/director Noah Baumbach (follow my tag for the director on this blog to read reviews for Greenberg and Frances Ha).

For those getting a little tired of Baumbach’s recurring theme of the challenges of growing old and letting go of youth, While We’re Young may disappoint, but it is worth sticking through for a confrontation with reality that is powerful as Greenberg fishing out the unrecognizable dead animal out of a house pool as younger people reveled around him. In While We’re Young, however, the moment feels more grounded, less metaphorical and ultimately, more disturbingly real. Baumbach still has that special touch for capturing moments resonant with revelation without coming across as heavy-handed. It’s a special kind of moment in cinema that few writer/directors can pull off (his hero Eric Rohmer comes to mind).

After the lengthy Ibsen passage, we meet middle age Gen Xers Josh (Ben Stiller) and his wife Cornelia (Naomi Watts), as they struggle to tell an infant the story of “The Three Little Pigs.” When both forget how the story goes, they begin to argue about their memory of it. Meanwhile, the baby bursts into tears. The implication is that these two are parents, but the child’s cries rattle them. Soon, their friends, the babe’s actual mother (Maria Dizzia) and father (Adam Horovitz — Ad-Rock of the Beastie Boys!), arrive to scoop their child up. It’s a cute play on perception and a quick, efficient device to establish these characters, who still haven’t found a way to come to terms with adulthood.

Though all their friends seem to be having children, it soon becomes apparent that Josh and Cornelia are in a mid-life crisis of arrested development. Josh is a documentary filmmaker with one well-received movie under his belt that’s out of print and so old that you can only find it on the secondhand market on VHS. He’s stuck in a rut with his follow-up, now about 10 years in the making and clocking in with a run-time of 10 hours that he cannot seem to pare down. Then he meets a 20-something fan, Jamie (Adam Driver), who melts Josh’s heart by admitting his fandom and saying he spent some stupid price on eBay to obtain an original VHS copy of the movie. They become fast friends.

Josh finds new vicarious youth in Jamie and his girlfriend Darby (Amanda Seyfried), and easily pulls Cornelia into hanging out with them. After all, Cornelia is stuck in her own rut. She still works for her father Leslie (Charles Grodin, in remarkable deadpan mode), a legend in documentary cinema who is more active than Josh. While Leslie accumulates awards, Josh struggles to find grant money to continue his work.

Stagnation is a big thing for the middle-aged couple, as Watts — stellar at balancing pathos and humor — reveals her character’s embarrassment about being in her 40s and working for her dad with leaden reserve. It’s a heavy regret, but she has found a way to live with it, yet you can sense her feeling that life has passed her by. At another point in the film she says about having a child, “We missed our chance … I’m fine with that.” There’s a sad acceptance to the statement. Thus, Josh and Cornelia embrace the vicarious opportunity that the millennial couple offers them as if they were salvation incarnate. Darby is an entrepreneur, marketing homemade ice cream featuring incongruous Ben & Jerry’s flavors of her own design. Meanwhile, Jamie aspires to make his own documentary films. The 20-somethings offer a new life. Who needs a baby when you have fully grown children to hang out with?

At first, Josh and Cornelia are delighted by this new breed of human they have discovered: young, prototypical Brooklyn hipsters who have re-purposed the detritus of Gen X and curated it in interesting ways. When Josh and Cornelia, stop into the earthy studio apartment of Jamie and Darby, they are confronted with racks of vinyl records, albeit mostly thrift store throw aways from the likes of Phil Collins and Lionel Richie. Cornelia observes, “It’s like their apartment is filled with stuff we once threw out, but it looks so good the way they have it.” It’s as though the new generation has co-opted their generation’s popular trash whose only merit is that it is “vintage.” Look, there’s a cassette of Meatloaf’s Bat Out of Hell on the dashboard of Jamie’s old sedan. As any grounded member of Gen X should know, that album was never cool. However, Josh is too smitten to notice these clues of phoniness. When Jamie plays “Eye of the Tiger” to get Josh pumped for a meeting with a possible investor in his film, Josh tells Jamie, “I remember when this song was just considered bad.” But he starts bobbing to it, and adds, “but it’s working.”

There’s a witty sort of dramatic irony going on here. The idea of sincerity is different for these two. While Josh says he is struggling to make “a film that’s both materialist and intellectual at the same time,” Jamie says he is looking to present “the truth” with his movie, which, as Josh will come to learn, does not necessarily mean being strictly honest in the literal sense. When Jamie volunteers to help Josh with his documentary, Josh will finally come to understand the gulf between them. Finally, he tells Cornelia about Jamie, “It’s all a pose. It’s like he once saw a sincere person, and he’s imitating him all the time!”

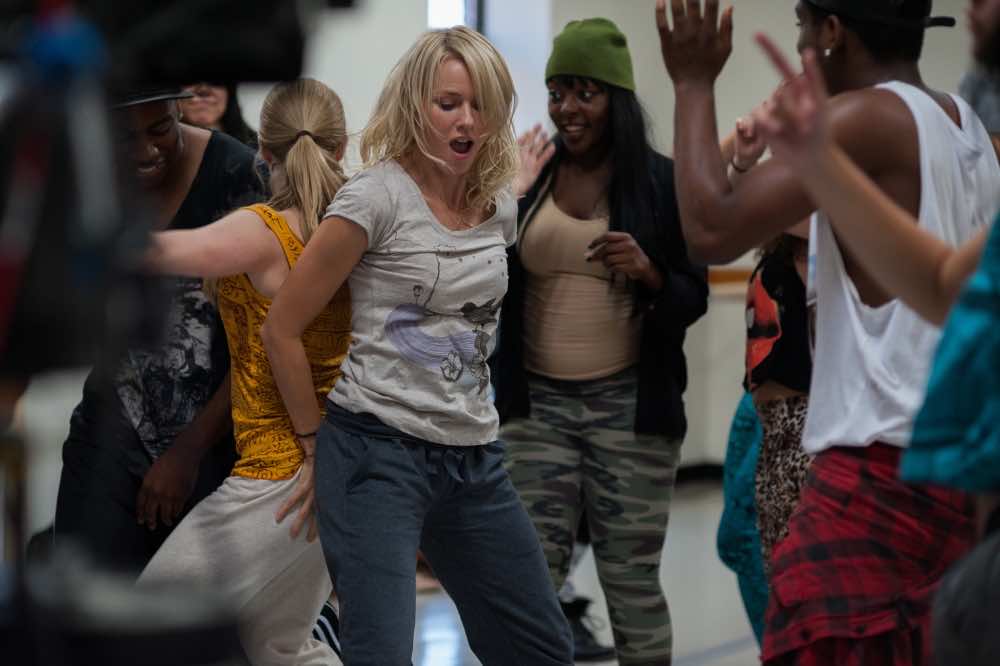

Josh is such a dynamically drawn character and Stiller brings an empathetic sincerity to his struggle via yet another richly written part by Baumbach. It’s a shame you cannot say the same about the women, who have issues and complexities of their own. Watts raises many small moments with Cornelia to impressive height, but the character’s standout moment with her friend/nemesis, Darby, happens during a hip-hop dance class, where she gradually finds her groove to awkward effect, played for cheap laughs. Even less fulfilling of a character is Darby whose character is hardly given a chance to transcend her artisanal ice cream flavors. Like Cornelia, it feels as though she is only along for the ride. That these women feel like supporting players in what should be an ensemble film is such a shame, especially considering how terrific the women characters were drawn in Baumbach’s previous movie, Frances Ha, featuring a screenplay he co-wrote with the film’s star, Greta Gerwig.

But maybe this is Josh’s movie for a reason. The fact that our hero is a filmmaker and male and is even more sympathetic than Stiller’s last role in a Baumbach movie (Greenberg), will make some wonder if Josh is a surrogate for Baumbach (the Internet has theorized might Jamie be a stand-in for director Joe Swanberg? In this radio interview, Baumbach denied this). It also takes a certain sense of self-awareness to pull this kind of movie off. One has to be ready to laugh about oneself, and Baumbach has always been fearless about that. That’s why, when the end finally arrives and Josh finally confronts Jamie, the film offers a brilliant play on perspective. As Josh’s father-in-law becomes accepting of Jamie and his vision of “truth,” Jamie warps into a stranger to Josh. In this resonant penultimate scene, Baumbach reveals how both base slapstick and intellectual wit can work together so brilliantly by playing with audience anticipation and textured characters.

Despite a final scene that feels a bit too tidy, While We’re Young examines the complexity of change from one generation to the next as a vicious cycle that never releases its grip unless you learn to make yourself comfortable in it. After all, the next generation is pursing all of us … “under a new banner, heralding the turn of fortune.”

While We’re Young runs 97 minutes and is Rated R (there’s cussing. Otherwise, teens can go and see what they have to look forward to at 40). It opened in the South Florida area on April 10 in many theaters. The indie cinema to support is O Cinema Miami Beach, which hosts the film until the end of this week. A24 Films hosted a press screening in Miami back in March for the purpose of this review.

loved frances ha from him. If this is half the worth of Frances and fantastic Greta in its role, it is a perfect movie…

Me too. Frances Ha was an easier film to love. This one, however, grew on me, so give it a chance.

will watch it for sure. Have you watched Ida from Pawel Pawlikovsky? A must of last year…

I have seen Ida! It was a favorite of last year for me. I was actually one of the first to see it. As such, I was able to review it for another a major film criticism site. You can find that review by doing a search for Pawel’s name, right here. Let me know what you think.

Yes, Ida is a superb piece of movie. Truly a great piece of cinema. The balance in between the artsy and the reality in regards the camera and watcher’s eye is complete. Will look up your review. Thanks.

PS: I am just cruising your site. I can say – wow. What an incredible array of cinema. Great site, Hans.

PSS: Have read your review of Ida. It is meticulous and very informative. Thanks.

Thanks for all the kind words. Have fun exploring my film reviews. There are a few films that have hardly received the attention to detail I give them.