It’s been 12 years since Bill Morrison came to Miami and blew the minds of a nearly packed house with Decasia in a large screening room at the Hyatt Regency in Downtown Miami as part of the Rewind/Fast Forward Festival. The 70-minute film was made up of clips from movies from the early 20th century printed on nitrate film that had succumbed to a state of decay as the nitrate began breaking down. Morrison went around the world looking for destroyed movies to bring back to life without any intention to restore them (they were beyond help) but to recontextualize them, rot intact.

With music provided by avant-garde composer Michael Gordon, Morrison strung the images together. It opens with a whirling dervish somewhere in Istanbul, spinning slowly to the metallic circular hiss of what may be a lightly scraped cymbal. The film builds from there, featuring waves crashing on rocks and globules of bubbled, corroded film seemingly overlaid on the image and a boxer jabbing at a strip of undulating celluloid. As the image itself comes apart, something new arises, as Gordon’s music pulses between a call and response of droning piano and tapped xylophones, the cymbal still hissing along. The movie builds with a pastiche of images as diverse as the patterns of decay Morrison found on the films, with Gordon’s music building repetitively, growing higher and louder as more instruments pile into the mix offering layers of harmony and counter melody.

The 2003 film has become legendary in the experimental film world and was registered at the Library of Congress in 2013 as one of the supreme examples of American cinema aesthetics, alongside Pulp Fiction and Mary Poppins. Morrison has continued to work with Gordon and has never stopped experimenting with film in decay, but he also shoots his own footage. Below you will find two fine examples of their work since Decasia, both of which were featured during a retrospective at the Miami Jewish Film Festival a few days ago (Bill Morrison and Michael Gordon to discuss and present their avant-garde films at Miami Jewish Film Festival). The first, “Light Is Calling” (2004) is a short that follows a similar construction to Decasia. Gordon first provided the music, a slow and sad violin solo to the soft pulse of a bell recorded backward as unrecognizable ambient hums pile up and melt away. Morrison culled images from a damaged print of The Bells (1926) by James Young to create an enthralling experience of sound and vision:

The next short is something completely different. Morrison handed cinematography duties to his cat in “Gene Takes a Drink” (2012), as the feline explored their garden. The perspective of grass and flowers and a fish pond via this “cat cam” is a revelation. Gordon’s playful music, though it sounds electronic, actually features cello, piano, guitar, double bass, clarinet, and percussion. The footage is sped up a bit to the music, adding another layer of new perspective, and then Morrison starts playing with filters on the image for yet another abstract layer, raising the film to another realm of transcendentalism by calling attention to the beauty of new perspective.

I point all this out to hopefully prepare you for tonight’s world premiere at the New World Symphony of El Sol Caliente, a near 30-minute “city symphony” by Morrison and Gordon dedicated to Miami Beach. As they usually work, Gordon first provided the music and Morrison cut his footage to it. “It’s typical of two other city pieces that we’ve done,” says Morrison, speaking from his home in New York. “Gotham being about New York and Dystopia being about Los Angeles, and it sort of comes from a tradition of city symphonies with Berlin: Symphony of a Great City or Manhatta.”

You can find a great overview of what a City Symphony is by reading this article (City Symphony Primer: 3 Essential Films to Watch Now), where you can stream Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand‘s Manhatta (1921) and the more epic Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (1927) by Walter Ruttman. “We’re sort of resurrecting that for the 21st Century,” notes Morrison, “but really drawing on 20th century archival imagery and then sort of as a refrain at the end, adding original, contemporary footage.”

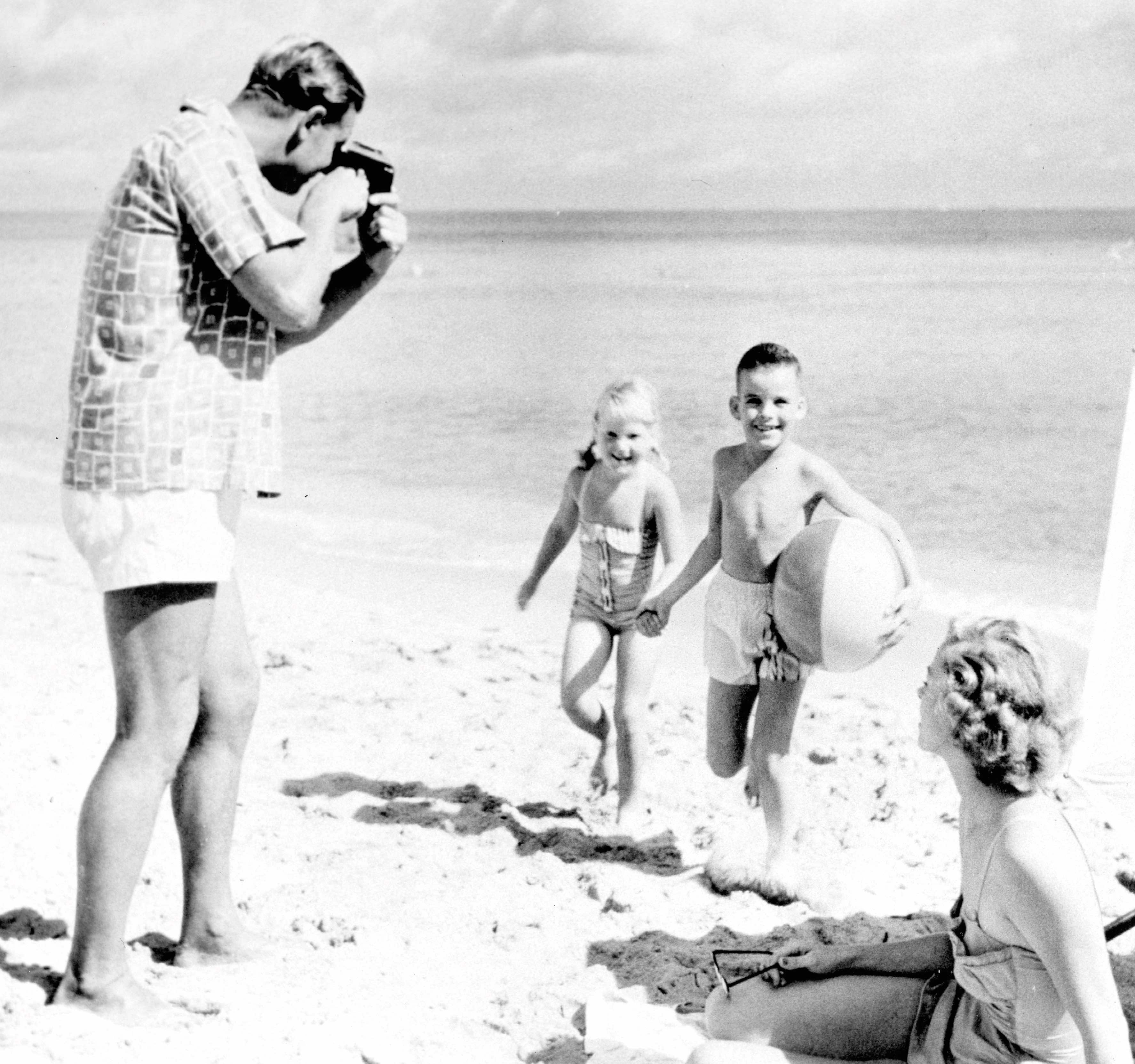

So you can expect images Morrison shot himself of Miami Beach as well as old footage he discovered. Though Morrison calls himself an “interloper” in Miami Beach, he has set his aim to present a version of the city outsiders would not expect. “You know, Miami Beach, at least the way it’s been portrayed throughout history, has been as a vacation land,” he says, “so it’s been a struggle to find imagery that isn’t about tourism, but it has any interesting portrait of the 20th century in that you have a lot of footage of the 1926 hurricane, you have the troops coming in and G.I.s taking over the Miami Beach hotels in the ‘40s for training, and then a lot of those guys end up coming back from the war and settling there, so it is an interesting cultural melting pot.”

He spent a lot of time in Miami and Miami Beach and offered a preview of some of the images he has assembled. “I walked through Art Basel with a GoPro on my chest,”  he says, referring to the Miami Beach-based international art festival that unfolds inside and around the Miami Beach Convention Center. “I got some nice scenes of people going up to a photo booth and posing.”

he says, referring to the Miami Beach-based international art festival that unfolds inside and around the Miami Beach Convention Center. “I got some nice scenes of people going up to a photo booth and posing.”

He also went outdoors, riding a bike with a Go-Pro camera on its handlebars and shot footage from the shore, which will provide a key element in the film. “There was a couple of full moon shots,” he notes. “I got a couple of full moonrises and sunrises over the ocean, and also I had a small drone camera, so I got some footage of the beach and the waves from a different perspective, so that footage I used to create chapters and a way in and out of the archival stuff.”

Morrison says he gathered lots of footage from various locations, including the Miami-based Lynn and Louis Wolfson II Florida Moving Image Archives, which happened to have been the main sponsor of the Rewind/Fast Forward Festival that brought Decasia to Miami all those years ago. “With the archival stuff,” Morrison explains, “I hit the Library of Congress for nitrate 35 millimeter to see what I could find on Miami Beach, and that was an interesting project. Then, with the new film stuff, a lot of it came from the Fox Movitone Archive at the University of South Carolina and then more locally the Louis Wolfson Archive … They are now located in a beautiful new facility at Miami Dade College, so I was working closely with them to come up with home movie footage, and some of that’s been really, really awesome.”

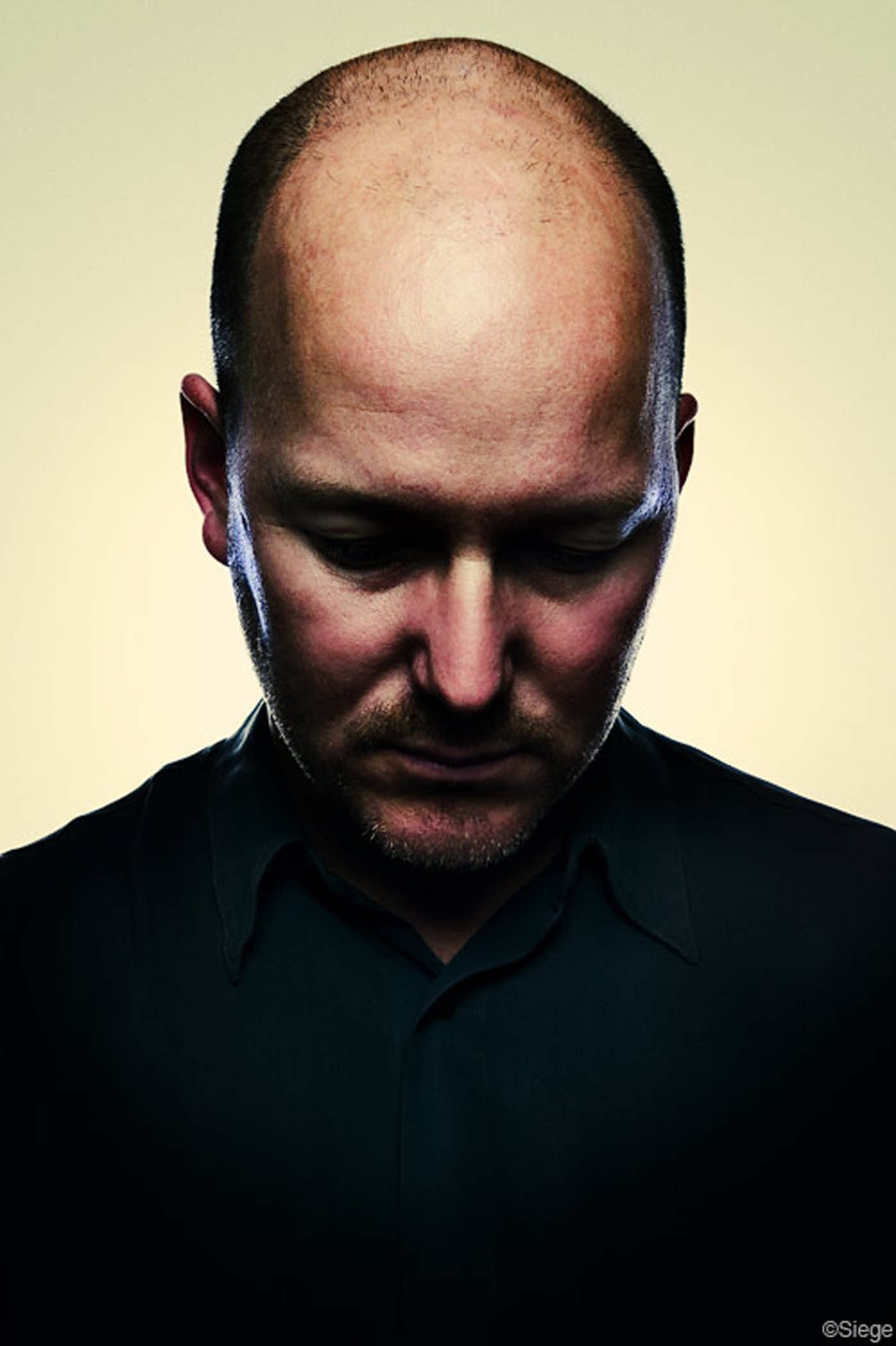

It is fitting that Gordon provided the glue to the images via his music for El Sol Caliente, which translates from Spanish to “the hot sun.” He has intimate knowledge of Miami Beach.  “My family moved there from Central America when I was almost 8 years old,” says Gordon, speaking via phone from Amsterdam, where he was visiting for a concert, “and I went to [Miami] Beach High, so I feel like I’m from Miami Beach, and this is kind of a wild, trippy thing to be doing, actually, going back to my town, working with the New World Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas, especially on this piece.”

“My family moved there from Central America when I was almost 8 years old,” says Gordon, speaking via phone from Amsterdam, where he was visiting for a concert, “and I went to [Miami] Beach High, so I feel like I’m from Miami Beach, and this is kind of a wild, trippy thing to be doing, actually, going back to my town, working with the New World Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas, especially on this piece.”

When asked about his memory growing up on Miami Beach, Gordon recalls an experience distinct to those who have lived a long time in the area: the weather. “I was talking to Bill and of course, he’s drawing on a lot of historical images of Miami Beach, but when I was thinking back to growing up in the area, all the time I spent there, the thing that influenced my thinking was kind of seeing this little, tiny strip of land, surrounded by this huge bay and then this large ocean and the crashing of the waves and the stillness of the waves and those sudden huge storms that happen every afternoon at 4 o’clock or something and then how it clears and how hot it becomes. It’s really more a feeling for the land and the climate and the forces of weather.”

Considering the weather, there is something even more ominous about the territory of Miami Beach, for, as with Decasia, a profound subtext arises in the juxtaposition of the film and music in El Sol Caliente. As some might be aware, scientists have warned it will not take long before sea-level rise erases Miami Beach (check out the graphic in this article). This was not lost on both the filmmaker and composer. Morrison says, “Though I don’t make an explicit reference to it, there’s also this overriding it: it’s a very fragile barrier island on a continental peninsula, all of which is at risk with rising ocean waters, so there is this sense that none of this is permanent.”

On Friday, January 30, and Saturday, January 31, the New World Symphony will present the world premiere of El Sol Caliente, a tribute to Miami Beach celebrating the city’s centennial by Michael Gordon and Bill Morrison as part of its “New Works” program. Tomorrow night is already sold out, but there will be a free, live “Wallcast” on the front of the NWS building for park-goers. For more information, visit nws.com.

[…] Hans Morgenstern talks to the creators of “El Sol Caliente” on the Independent Ethos media blog. It’s the best preview going of what concertgoers at tonight’s sold-out performance will see and hear. Here’s the story: https://indieethos.wordpress.com/2015/01/30/michael-gordon-and-bill-morrison-talk-about-their-miami-beach-city-symphony-el-sol-caliente-an-indie-ethos-exclusive/ […]

[…] third installment of his City Symphonies El Sol Caliente with filmmaker Bill Morrison premiered in […]