Before the very first stark image hits you, Fury director David Ayer unnerves the audience with a simple title card describing the all-out war they are about to witness. The text establishes this is 1945, the end of World War II and U.S. troops are advancing on Berlin. Hitler’s forces are down to recruiting children and old men to fight, but they still have tanks that outgun the comparably puny Shermans of the U.S. army. Then the land fades up from black. It’s all gray and black mud, destroyed war machines and crumpled, muddied bodies. The camera tracks and tracks across this for enough time to set up that this is not a film out to glamorize or romanticize war but to present it as stark and as harrowing as Hollywood can.

Before the very first stark image hits you, Fury director David Ayer unnerves the audience with a simple title card describing the all-out war they are about to witness. The text establishes this is 1945, the end of World War II and U.S. troops are advancing on Berlin. Hitler’s forces are down to recruiting children and old men to fight, but they still have tanks that outgun the comparably puny Shermans of the U.S. army. Then the land fades up from black. It’s all gray and black mud, destroyed war machines and crumpled, muddied bodies. The camera tracks and tracks across this for enough time to set up that this is not a film out to glamorize or romanticize war but to present it as stark and as harrowing as Hollywood can.

For the most part, Ayer succeeds. Forgiving an early sequence that tries too hard to reveal the heart of Brad Pitt’s character Don “Wardadddy” Callier, where he frees a horse from an SS officer, the film’s power lies in its ability to present the unforgiving quality of war. Soldiers are burned alive and torn apart. Faces are removed and bodies burst below tank tracks. These events of horror occur in the film’s first 20 minutes. “This ain’t pretty,” Don tells his new, fresh-faced co-pilot Norman (Logan Lerman). “This is what we do.”

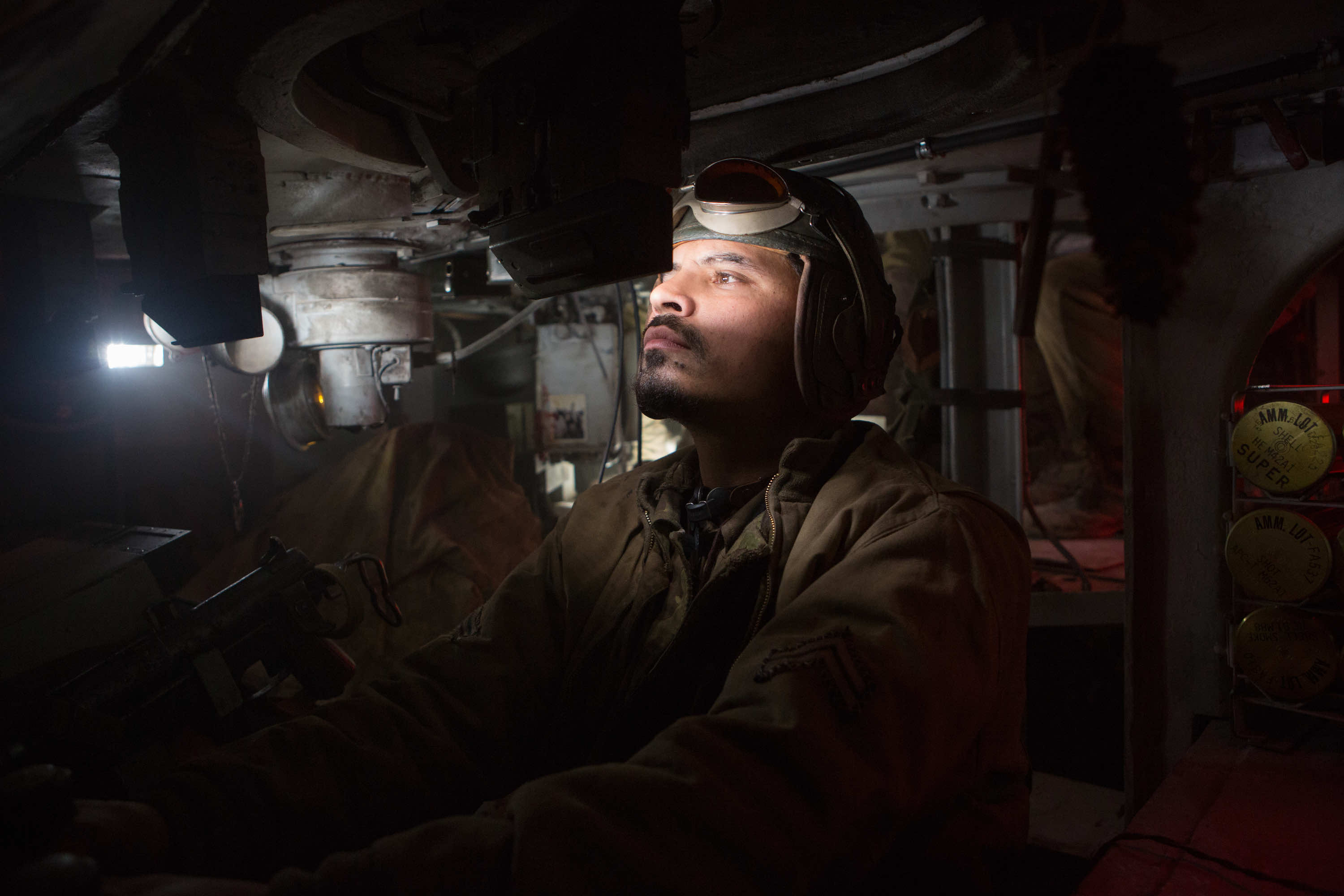

Ayer not only stages vicious battles and skirmishes but presents aftermath as horror: stacks of squishy, gelatinous body parts quivering in rumbling truck beds and even a bit of stiff, pancaked human road kill. He does it all in sharp, steady deep focus. Unlike Spielberg, who, in Saving Private Ryan, stylized  his presentation of war violence by enhancing the imagery with tints, shaky camera movements and ratcheted shutter speeds, Ayer wants to present something more unadulterated. Even the interior of the titular tank is far from romantic. Besides photos of loved ones, there is nothing but cold, hard metal bits, much of which blocks out the faces and bodies of the five-member tank crew. They have been consumed by this machine and are only partly human. They are family and hive with various capacities in making “Fury” run while trying to cling to their individual tiny, salvageable bits of humanity.

his presentation of war violence by enhancing the imagery with tints, shaky camera movements and ratcheted shutter speeds, Ayer wants to present something more unadulterated. Even the interior of the titular tank is far from romantic. Besides photos of loved ones, there is nothing but cold, hard metal bits, much of which blocks out the faces and bodies of the five-member tank crew. They have been consumed by this machine and are only partly human. They are family and hive with various capacities in making “Fury” run while trying to cling to their individual tiny, salvageable bits of humanity.

All actors deserve nods for realizing their characters. Michael Peña’s Mexican character, Trini Garcia, nicknamed “Gordo,” the tank’s driver, handles anxiety with cool determination. Don refers to Jon Bernthal’s Grady “Coon-Ass” Travis as an animal when we meet him trying to fix a broken-down “Fury” on a smouldering battlefield. Bernthal infuses Grady with an unstable sort of menace, even when he tries to show affection to his mates by tugging at their ears and noses. Then there’s Boyd “Bible” Swan played with tortured heart by the too often underrated Shia LaBeouf. His Bible-quoting could have easily been a contrivance had LaBeouf not brought such expressive heart to his character. He’s a focused psychotic but also has great affection for those in his company. Sadness and anger with righteous Christian logic used to rationalize behavior never appeared more conflicted.

Yes, they are a motley crew, but to fault the film on that means you should fault all ensemble adventure films for such tropes since John Ford’s Stagecoach. It’s Ayer’s unflinching sensibility that makes the film stand out as a statement film because this is not entertainment. This is a nerve-rattling confrontation with the sublime. The tank battles are not CGI, and the effect only enhances the weight of their power on soft humans — both internally and considering the unforgiving science of visceral matter. Ayer’s only enhancement to the tension is a score by Steven Price featuring swelling, rhythmic horns, voices and timpani and bass drums, but it’s plenty enough to tune into for the sense of dread the director is trying to present with this anti-war film.

We follow these men as they show little mercy to surrendering SS troops, the most fanatical of Hitler’s military. Early in the film, Don gives Norman, who was a mere Army typist before being sent to the front, a brutal lesson in killing. After taking a town “decorated” with bodies of hanged children with signs around their necks dubbing them cowards, Gordo mows down an unarmed, surrendering SS officer alleged to have committed the atrocities. Then, one splice cut later, he makes out with a now gracious, liberated fräulein. The boys can have a civilized extended meal at the home of two rattled women, and Norman can have a moment to fall in love. But nothing quiet can last in this all-out war. So the mood can be brought down when Fury’s crew brings up France and their methodical execution of scores of wounded horses, and then there’s worse… the return to killing for their lives.

a now gracious, liberated fräulein. The boys can have a civilized extended meal at the home of two rattled women, and Norman can have a moment to fall in love. But nothing quiet can last in this all-out war. So the mood can be brought down when Fury’s crew brings up France and their methodical execution of scores of wounded horses, and then there’s worse… the return to killing for their lives.

The brutality of the end of World War II was harsh. I’ve heard stories from my father who was forced into the Wehrmacht at 16 years old, when his family tried to flee to Spain. It was that or face a firing squad. He survived Africa and Stalingrad (I’m still looking for a translator of his diaries from that era as pictured in the following post: Bonding with the filmmakers of ‘The Book Thief’ over my father’s German WWII story). I’m glad that Ayer did not turn this film into some fluffy adventure movie. You might nitpick the characters, but the real star of this film is violence and the strain for humanity to break through it. The culminating skirmish that ends the film speaks to both random luck both good and bad but also a little more: a sense of hope for the only strategy that can end wars: just stop fighting.

Fury runs 134 min. and is Rated R (it’s one of the most justifiably, unflinchingly violent films I’ve seen in years). It opens today at your local multiplex. Sony Pictures invited me to a preview screening for the purpose of this review.

The book thief was not based on a real life story. It was certainly nothing like the gritty reality that you describe in your review of ‘Fury.’ It’s a nice thought that we’ve all had at one time or another, but the reality is that having Europe sit on its hands and refuse to fight Hitler and his murderous henchmen wouldn’t have stopped world war 2.

Fury is definitely more in line to the stories I heard from my father. Book Thief is based on stories the author heard from his grandparents. These are both fictions but they still both capture the randomness and suffering on ordinary people caught up in the war. I do understand the inevitability you speak of. We can’t forget World War I.