The way Brontis Jodorowsky explains it, his father’s new film, The Dance of Reality, is much more than a cinematic adaptation of the memoir of the same name. After all, his father, Alejandro Jodorowsky, is the man behind “Psicomagia” (Psychomagic), a form of therapy through art. His memoir, published in Spanish in 2001, stands as an example of that. Though it features cruel stories of abuse the director suffered as a child, it is less a fact-based memoir and more an “imagined autobiography” that becomes a sort of redemption for his family.

The way Brontis Jodorowsky explains it, his father’s new film, The Dance of Reality, is much more than a cinematic adaptation of the memoir of the same name. After all, his father, Alejandro Jodorowsky, is the man behind “Psicomagia” (Psychomagic), a form of therapy through art. His memoir, published in Spanish in 2001, stands as an example of that. Though it features cruel stories of abuse the director suffered as a child, it is less a fact-based memoir and more an “imagined autobiography” that becomes a sort of redemption for his family.

Speaking via Skype from his home in Paris, Brontis, who in the film plays the role of Jaime Jodorowsky, the grandfather largely responsible for the traumatic upbringing of his father, offers insight into the film and the purpose of it as mystical therapeutic device. He speaks soothingly and builds on his statements explaining the psychomagic behind the film. “I have my father, the public figure that you know. He’s my father. But I also have another father that is the private man, and I also have another father, which is the archetype of the father inside of me that is built up with Jaime, Alejandro and also with me being a father. So there’s a father figure composed by different experiences, and inside this father figure, we have this very negative part, character, father figure, that’s only negative. That was Jaime, my grandfather. So by doing this process of remaking the story and giving him a chance through the movie to humanize, to take off the costume of the domestic tyrant and open his heart, we transform a negative part of the father archetype in our family story into a character that is not a saint but has a different aspect and that can change, you see, that can progress. A heart can be opened, so the father figure in our family tree, genealogy, changes, so we’re transmitting to our children and grandchildren another vision of what the father is.”

The bond between Alejandro Jodorowsky and his son is profound. It comes out beautifully in this new film, the director’s first feature in 23 years. It also comes out in a documentary about the director’s efforts to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune as a movie. Jodorowsky’s Dune captures one particularly raw moment where the elder  Jodorowsky seems still a bit haunted by the fact he had his the 12-year-old son train for years to prepare for the part of Paul Atreides, yet the film was never shot (Brontis calls this an example of a “private message” from his father). Brontis looks on the bright side. “Yeah, well, you know, what I acquired during those two years of training was so useful afterwards in my actor’s life, especially all the [physical] training part because that taught my body to learn, which is the most important thing that you can learn: is how to learn, so afterwards, when I went to do theater, I always worked in a very physical type of theater. My body was always involved, but I had a trained body that could learn … It was not a waste of time.”

Jodorowsky seems still a bit haunted by the fact he had his the 12-year-old son train for years to prepare for the part of Paul Atreides, yet the film was never shot (Brontis calls this an example of a “private message” from his father). Brontis looks on the bright side. “Yeah, well, you know, what I acquired during those two years of training was so useful afterwards in my actor’s life, especially all the [physical] training part because that taught my body to learn, which is the most important thing that you can learn: is how to learn, so afterwards, when I went to do theater, I always worked in a very physical type of theater. My body was always involved, but I had a trained body that could learn … It was not a waste of time.”

Jodorowsky’s cinematic version of Dune would have been the first ever attempt to adapt the 1965 novel. Though Jodorowsky made great efforts to gather collaborators like H.R. Giger, Orson Welles, David Carradine and Pink Floyd as just some of his “creative warriors,” every Hollywood studio he presented his grand treatment, which included the script by Dan O’Bannon, storyboards by comic book artist Moebius and lots of detailed concept art by Giger and and Alex Ross, they balked at his ambition, which included no fixed limit to the film’s runtime. “They were afraid of him,” says Brontis, “of his personality, so it wasn’t a problem that it was two hours, three hours or five or 10. How long is Star Wars? Too long, much too long.”

Brontis continues, noting that there was also a fundamental cultural conflict between the source of Jodorowsky’s unrestrained creativity and Hollywood’s bottom-dollar attitude. “Also, I think this is an American thing, that Americans don’t want the success to come from outside, so I think that in a way, they saw the project, but I can’t be sure of this, maybe it was just paranoia, in a way,  I sense they saw the project, and I think they saw that, wow, maybe that would be a kind of future for movies, and they said, well, why give it to him? Let’s take the ideas and do it ourselves. Instead of doing one movie, we’re going to do this, that and that … I think it’s part of the movie industry’s history. It’s a world of artists and crooks at the same time, of people who dream wonderful things and big bank accounts both at the same time,” he says with a laugh.

I sense they saw the project, and I think they saw that, wow, maybe that would be a kind of future for movies, and they said, well, why give it to him? Let’s take the ideas and do it ourselves. Instead of doing one movie, we’re going to do this, that and that … I think it’s part of the movie industry’s history. It’s a world of artists and crooks at the same time, of people who dream wonderful things and big bank accounts both at the same time,” he says with a laugh.

Despite all that, the future has been good to the Jodorowsky family, and you will be hard pressed to find a creative clan with a more positive and creative drive, fulfilled with their place in the universe. Brontis has mostly worked in theater, but only recently returned to cinema. In 2012, he acted in Táu, a film shot in the same Mexican desert where his father shot El Topo, in which the younger Jodorowsky made his acting debut alongside his father. With Táu, under the direction of Daniel Castro Zimbrón, for the first time in his life, Brontis took the lead role in a movie. The collaboration went so well, they plan to begin a second film together, later this year. “Now we’re going to do another one that we start shooting in November or December that’s called the Darkness,” he reveals. He notes that it has already been work-shopped at Morelia, Toulouse and most recently at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

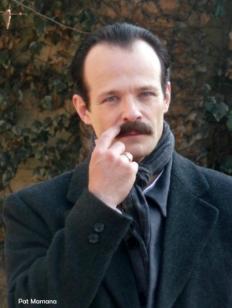

During his visit to the Miami Beach Cinematheque, he will introduce Táu at a rare U.S. screening, as the film was never picked up for distribution in the United States. Then it’s on to Speaking In Cinema, an hour-long chat with “Village Voice” film critic Michael Atkinson and “Miami Herald” film critic Rene Rodriguez , who both wrote their own positive reviews of The Dance of Reality (click on their names to read their articles).

It will be interesting to watch how the critics work with Jodorowsky, who says he is looking for having a little more time to deal with questions for Dance than usual screenings allow. “I’ve done quite a few festivals now, and there’s always a Q&A,” says Brontis, “but sometimes it’s just 20 minutes, so I just have time to answer one question.

There is much more with both Jodorowskys in other articles I’ve written. The titles of the articles below are hot links where you can read more (except for Alejandro’s quotes, no quotes overlap):

Brontis Jodorowsky to Speak in Miami Beach: “Miami Must Have Some Rock ‘n Roll”

Pure Honey Film Bits: Jodorowsky

Alejandro Jodorowsky replies to my questions via email, Part 2 – Spanish version

Alejandro Jodorowsky on Dune Documentary: “There’s Nothing Crazy About a 14-Hour Film”

Legendary Director Alejandro Jodorowsky on The Dance of Reality, Dune, and Fatherhood

The of course, there are the reviews:

Jodorowsky heals psychic wounds with fabulist recreation of childhood in ‘Dance of Reality’

Film Review: ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune’ celebrates the creativity necessary to do justice in sci-fi cinema

This interview was done to coincide with this weekend’s second installment of “Speaking In Cinema.” Both Jodorowsky’s Dune and The Dance of Reality are now playing at the Miami Beach Cinematheque, which is hosting the event. Brontis Jodorowsky will present The Dance of Reality in person on June 14. On June 15, he will also introduce Jodorowsky’s Dune and Táu. On Tuesday, June 17, at 7 p.m., Brontis will join “Village Voice” film critic Michael Atkinson and “Miami Herald” film critic Rene Rodriguez for the Knight Foundation-sponsored series “Speaking In Cinema” to discuss this film and other works by Jodorowsky. A meet-and-greet party at the Sagamore Hotel ends the night. Tickets for each screening and the event can be found by visiting the calendar page of mbcinema.com.