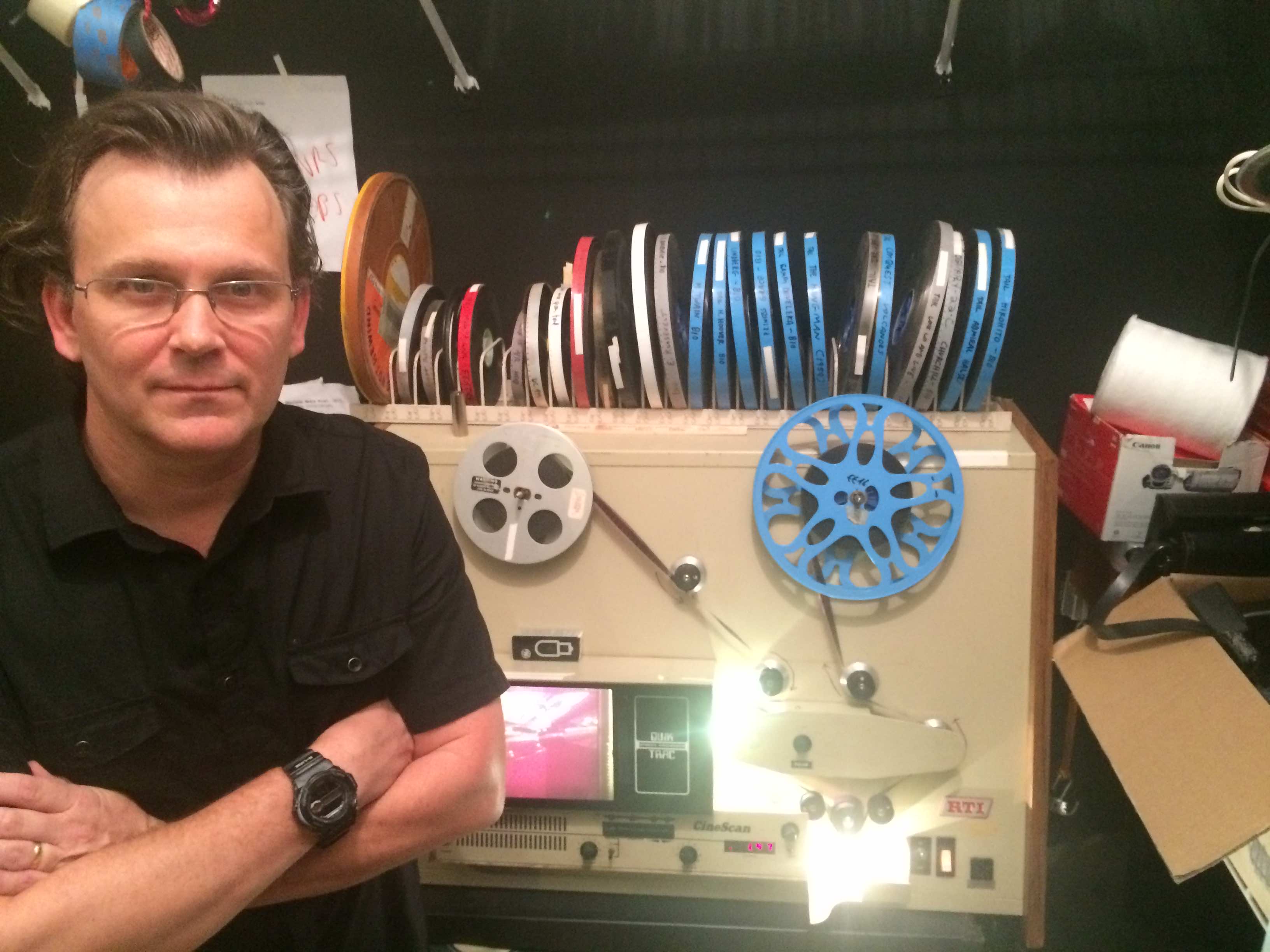

The past, nostalgia, memories and history are all very distinctive things, but embodying it all is Obsolete Media Miami. Called OMM for short, the space houses a variety of once mainstream mediums, from film to VHS cassettes, now deemed “obsolete.” Its home is located on the second floor of a building in Miami’s Design District, up a stairwell that smells like an old high school. The vintage scent befits a place like OMM, which also features equipment that was once ubiquitous in high school AV rooms, like 16mm projectors (pictured above) and slide projectors.

Co-founder Barron Sherer admits he was that AV kid who helped run educational films through those kinds of projectors in elementary school. Meanwhile, his partner at OMM, Kevin Arrow, admits that, as a child, he gained a reputation around his house for making collages from his father’s home movies with an old film reel of a 1940s Batman serial. “It kinda irritated my parents,” he admits.

The duo sit around a long, wide communal table at the center of OMM, surrounded by shelves and stacks of an array of equipment against the walls around them. Someone has put on side 1 of Radiohead’s OK Computer on a record player. Arrow has a smooth bald head and Sherer a thick, fluffy mane. Both are be-speckled family men in their with a long history in Miami’s art scene. Arrow is in his early 50s and Sherer, in his late 40s. Arrow projected slides at nightclubs on Miami Beach in the ’90s and Sherer was the long time programmer and director of the Rewind/Fast Forward Film & Video Festival in the early 2000s. Both also had important roles in the Alliance Cinema, an art house located on Miami Beach’s Lincoln Road Mall in the ’90s. But his merely scratches the surface of the mutual past of these self-described “film practitioners.”

They recently naturally gravitated toward really working together, including hosting multi-projector screenings of everything from home movies at art galleries to presenting laser light shows at the Miami Museum of Science (currently being reconstructed as the Patricia and Phillip Frost Museum of Science). They found a space to put their collection of stuff (Barron is the movie reel guy and Arrow the film slide guy) in April of 2015, creating OMM.

They admit that there’s little rhyme or reason to the organization inside the space right now. Along most of one wall and in front of a large panel window facing west, lies boxes upon boxes of Arrow’s slide collection that almost reach the ceiling. There’s also a lighted table, several carousel projectors and a Telex Caramate Slide Projector 4000 that allows you to enlarge slides on a large built-in screen. OMM’s slide collection also includes several binders of larger format slides from planetariums thanks to connections he has nurtured through his job in charge of collections at the Frost Museum of Science.

Arrow estimates he has about 80,000 to 100,000 slides in his collection, the most precious of which he keeps in a large wooden glass paneled table. “Slides that are important to me that I don’t have a project for end up in this box,” he notes.

“Barron’s domain,” located almost triangularly across from the slide collection includes a cumbersome film editing suite from the ‘60s, just waiting for an artist to get to work on it. In a room with more modern editing equipment, he has shelves and shelves of small film cans and boxes of Super 8 Bolex cameras used in OMM’s Super 8 boot camp.

In another far corner of the room, there are two, five-foot tall stacks of film cans containing what Sherer believes are Greek films from the ‘60s and ’70s that a Greek film producer left him because he had to skip town. Sherer does not know what became of the man, but now he has a treasure trove of Greek cinema, much of it mislabeled, waiting to be discovered once he gets to unspooling them. Some even look as though they may have never been played.

The name of their organization, which won a Knight Foundation grant last year, means a lot. It gave them a brand and an identity that has sparked awareness from all corners. Though the two of them brewed the name up offhandedly, it caught the attention of institutions like Florida International University and the Bass Museum, who have donated media and equipment to OMM no longer in circulation at their institutions. OMM also provides assistance to museums and institutions looking to exhibit rarely used mediums. Last year, when the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, which is located nearby, needed someone to project a 16mm film loop of the art of Paul Sharits, they called OMM.

“We’ll do the weirdo AV rentals for the PAMM or ICA now,” says Sherer. “When they have to show 16mm or whatever, they’ll call. We’ll do a tech job.”

OMM has a looper system that it rents out to galleries and museums. Arrow says, “It’s always been au currant for these contemporary artists to use 16mm film.”

In an interview I wrote for The Miami New Times, legendary filmmaker Jonas Mekas espoused the importance of OMM, calling it “very necessary and very important.”

“We cater to the art world, as opposed to just bringing them a projector,” notes Arrow.

If by now you haven’t noticed, these guys also have a deep-seated passion, making them ideal marketers for their jobs. Sure there are rental houses, they say, but nowhere else would you find two people as excited about media as Sherer and Arrow.

“We give them a little more because we promote the hell out of it,” adds Sherer, “so if ICA goes with me and you, we’re going to be talking about it for two weeks on social media whereas a rental house…”

“… might do nothing,” Arrow says, completing Sherer’s sentence.

Asked to look deep into what’s so attractive about working with physical media, they struggle a bit to look beyond their personal passion, which dates far into their formative years as children. As the Radiohead record spins toward its end, I prod them. They latch on to something that has been taking hold over the past decade, for instance millennials getting over iPods and into vinyl records.

“It’s a deeper connection,” says Sherer. “It’s what young people are looking for now. It’s why they buy an LP instead of downloading from iTunes … People think it’s a nostalgia trip, but it’s not,” he adds.

“It’s kind of interesting having to grow up without those fetishy, tangible things,” chimes in Arrow. “It’s just weird because the minute this gets turned off,” he says picking up a ringing iPhone, “a whole flow of content sort of stops, and they’re just in some weird matrix where everything has fallen away. There’s nothing there.”

“It’s also not finished,” Barron says of the easy-to-edit and ever flowing digital world of cyberspace. “It’s not complete. It’s living, changing. It’s morphing all the time.”

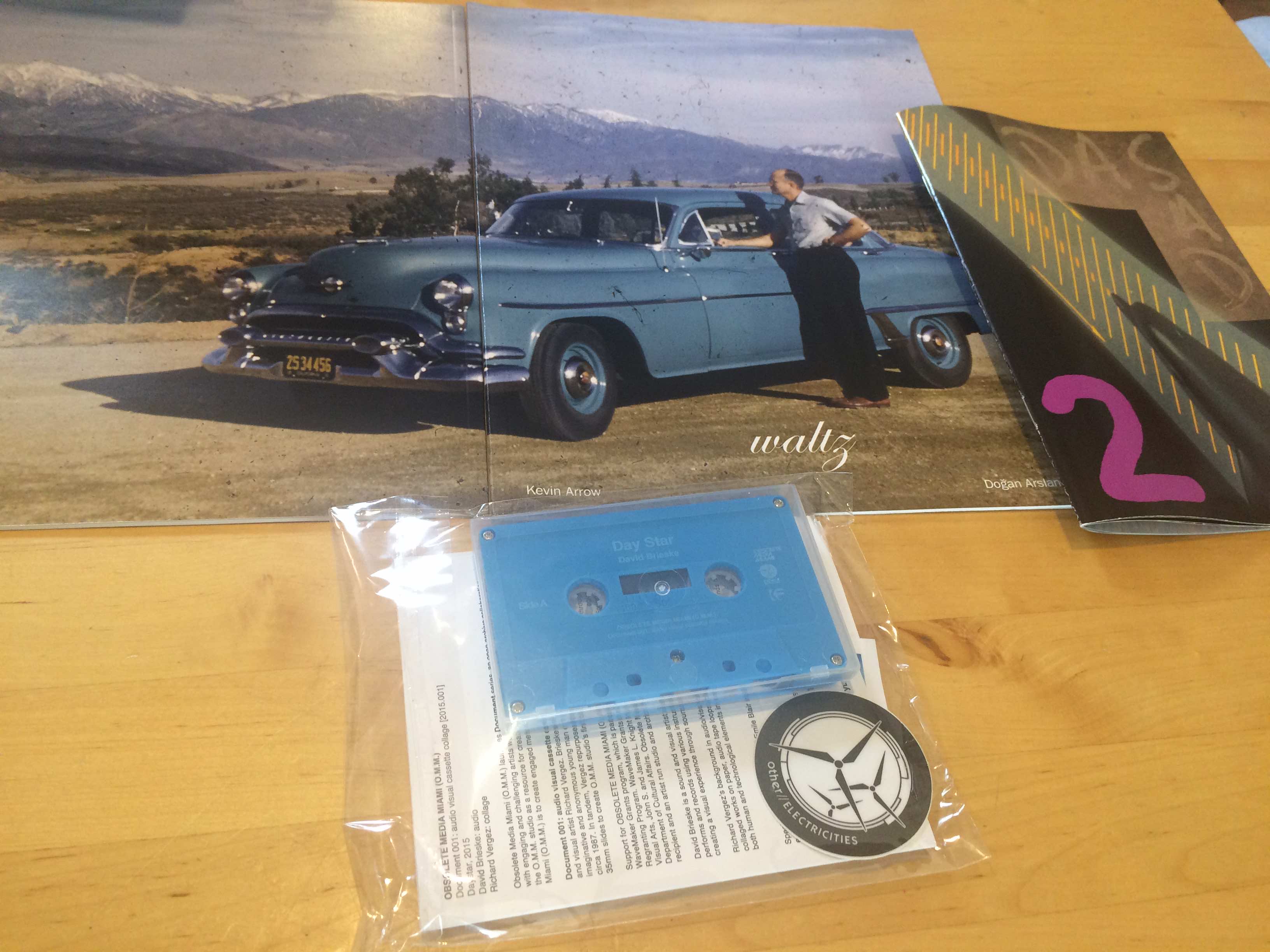

As an example of how against the grain of digital these guys are, Sherer has even gone through the trouble of transferring his Instagram account to 16mm film. Besides creating their own artwork, which often originates from garage sale excursions or visits to Goodwill, OMM is also now releasing collaborations with other artists. They have two issues of a “zine” out now, called “Document,” which can come in an array of formats. The first was limited to 250 and included collage work by local artist Richard Vergez and music by David Brieske on an audio cassette featuring a found audio recording of someone describing the sunrise. The second issue was limited to 70 and is a full color booklet detailing some of the contents at OMM by Danny Clapp and Juan Gonzalez. The duo also composed a soundtrack available on Soundcloud under their musical alias Das SaD, which can be unlocked via a password included with the booklet.

Describing how these documents are put together, Arrow says, “It’s a curated process where we invite the artist and the musician to come and work in the studio, and we give them a nominal budget and complete territorial and artistic control.”

Though not part of the document series, Arrow also released a large format booklet called Waltz, 2015, a collaboration between him and Miami artist Doğan Arslanoğlu. “Doğan expressed an interest in making print publications based on my slide archive,” explains Arrow. Waltz, 2015 marks the first in what is to be a series of curated selections from OMM’s 35mm slide collection. It was limited to only 50 copies and came out in December of 2015. All these “documents” are pictured above.

From offering a home to obsolete media, to providing assistance in the presentation of said media at museums and galleries, to giving everyone from established artists to amateur filmmakers a space and tools to work with, OMM keeps alive a different sense of working with media. It’s all well and good that the digital world has allowed for short cuts, but there is something precious about the deliberate and sometimes painstaking work demanded of physical media. OMM isn’t just preserving old stuff, it is preserving a way of life and its inimitable expression, something invaluable and far from obsolete to the art world.

Some images in this post were provided by Barron Sherer. Hans Morgenstern snapped the images of the men with their media and the images of the “documents.” OMM still has copies for sale of Document 001, which you can purchase by jumping through this link.

[…] By Hans Morgenstern, IndieEthos.com […]

Are there multiple versions of the Caramate 4000?

Some mention having sound or auto focus, so I’m wondering if these were optional add-ons to the basic model number, which stayed the same?

thanks

Hi Charles:

The short answer to your question is Yes, there are multiple versions of the Caramate 4000 and multiple companies that made them. Although I have not done indepth research I do know that Kodak, Singer and Telex all manufactured similar and in some instances identical looking audio viewer projectors. The Kodak Ektagraphic Audio Viewer Projector Models 470 and 250 came with a built in cassette players as did the Singer Caramate.