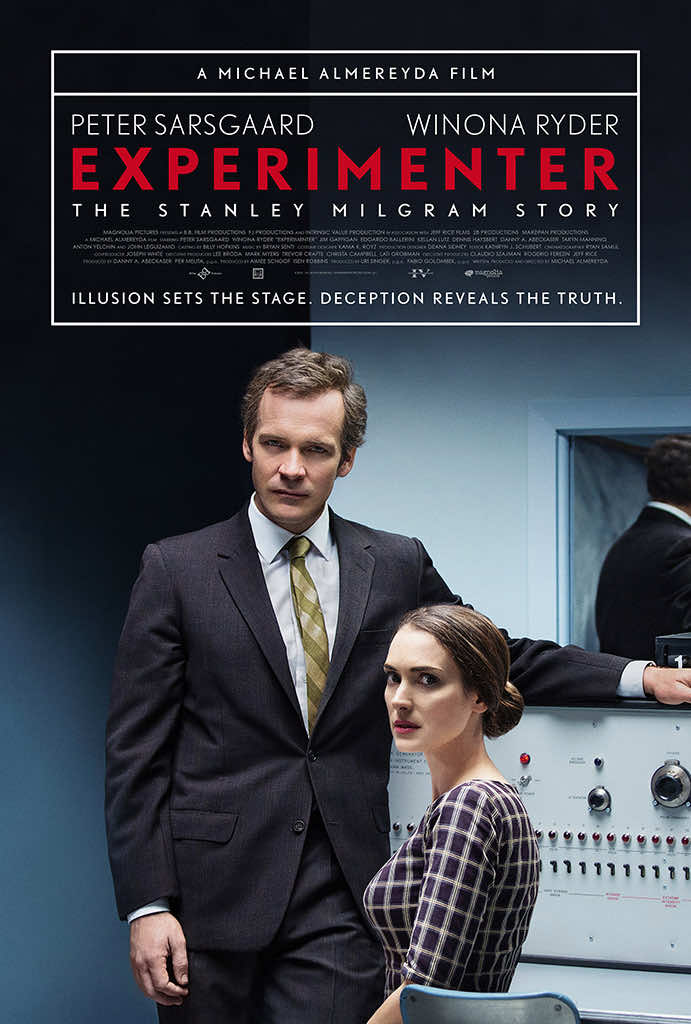

With Experimenter, American indie filmmaker Michael Almereyda returns in amazing form, tearing into the conventions of the biopic. The films follows the life of Stanley Milgram with a marvelous Peter Sarsgaard giving an archly arcane performance in the leading role. Rather than probing into his entire life, the film captures the uneasy relationship society has with Milgram’s still intriguing early ’60s experiment on authority and obedience. More than that, in the film’s best bonus, Experimenter does something interesting with the medium of cinema that speaks to Milgram’s penchant for deception or — what his character in the movie often repeats — illusion. It treads all over the fourth wall of cinema, coming across as more of an essay about society’s interest in Milgram’s experiments rather than a bio pic.

With Experimenter, American indie filmmaker Michael Almereyda returns in amazing form, tearing into the conventions of the biopic. The films follows the life of Stanley Milgram with a marvelous Peter Sarsgaard giving an archly arcane performance in the leading role. Rather than probing into his entire life, the film captures the uneasy relationship society has with Milgram’s still intriguing early ’60s experiment on authority and obedience. More than that, in the film’s best bonus, Experimenter does something interesting with the medium of cinema that speaks to Milgram’s penchant for deception or — what his character in the movie often repeats — illusion. It treads all over the fourth wall of cinema, coming across as more of an essay about society’s interest in Milgram’s experiments rather than a bio pic.

The film opens with a dramatization of how Milgram’s most famous experiment unfolded in terrific dramatic detail. For those unfamiliar it, it’s almost worth not spoiling because of the humor and tension Almereyda and his cast infuse into the scene, which takes place at Yale in August of 1961. It’s a famous scenario, however, still referenced in both popular culture and psychology. In this scene, Anthony Edwards plays the “teacher” and Jim Gaffigan the “learner.” A man holding a clipboard and decked out in a gray lab coat (John Palladino) instructs the teacher to teach the learner pairs of simple words he’s supposed to recall via multiple choice questions. Should the learner answer wrong, the teacher would deliver an increasing amount of electric shocks to him.

The illusion is that the learner is an actor who is not getting shocked at all, despite the screams of pain coming from behind the wall that separate the teacher and him. If the teacher hesitates, the man in the gray coat, also an actor, who sits at a desk behind the teacher, pushes him to “please continue.” In actuality, the teacher is the subject, duped into thinking he is assisting in an experiment involving the learner. Milgram, who was Jewish, was inspired by Nazi Germany and interested in seeing how far people would go to obey authority, even if it meant inflicting pain on another person. After publishing the results of his social experiment on obedience to authority, Milgram received strong criticism, but the test continued to have relevance. Experimenter does a riveting job explaining all this via a biopic so aware of its artifice as a film that Sarsgaard spends as much time looking into the camera and addressing the film’s audience as he does interacting with fellow actors. It’s a tactic that is only one of several cinematic strategies that makes the audience aware of illusion.

With its drab palette of brown, green, gray and punches of blue, the film features varying degrees of artificiality, the most extreme of which involve archaic blue screen used to dramatize a car in motion. There is also a scene that seems to take place on stage but is supposed to be the interior of Milgram’s mentor’s home, Solomon Asch (Ned Eisenberg). Milgram, with his wife Sasha (Winona Ryder), visit for tea where Milgram and Asch face off over differing approaches to the same ideas. The backdrop is made of old black and white photos of the interior of the home. It speaks to how Milgram feels about Asch: a bit nostalgic but also a sense that his ideas are dated. The effect of illusion speaks to Milgram’s mentality while also working on another level as a film trying to defy the conventions of the biopic, presenting even sentimentality as artificial.

You don’t have a sense that Almereyda is trying to defend nor indict Milgram, much less romanticize him. It presents his story, but above all, shows an interest in the concepts that have come to define Milgram as a social scientist who did more than this one experiment (we also see his connection to the concept of “sex degrees of separation” and his inspiration via “Candid Camera”). Experimenter is the illusion of a man masquerading as a reality. Skaarsgard’s strange, distant performance speaks to the lack of trust that came to define the real man but also brings him closer to the audience in a way few bio pics ever make their subjects conceptually tangible. Yet, despite Milgram addressing the audience for much of the film, he remains an enigma, a symbol of the vanity and intrigue this experiment still generates. The film seems to implicate those aware of the experiment’s element of deception and the curiosity it generates should they be placed in the role of the duped “teacher.” It’s the weirdest sort of Catch 22 that speaks to the charms of this experiment in the annals of the history of social psychology.

Ironically, the destruction of the fourth wall in narrative filmmaking presents Milgram as a warmer character than he should ever be. It fits his character brilliantly. There is so much debate of illusion in the film that if it doesn’t work as a critique or a celebration of the experiment, it at least works as a film that is not afraid of revealing the illusion of film as a replacement for a real-life story and especially a life lived for 51 years with an influence beyond death. A quote from Kierkegaard appears more than once in the movie: “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” Experimenter becomes a lesson in hindsight and the artificiality of the filter of our present, looking back. It’s idealized but also phony. In the end, the film teaches us to be careful about any lesson.

Experimenter runs 98 minutes and is rated PG-13 (for some language and psychologically traumatic situations). It opened this weekend in our Miami area exclusively at the Bill Cosford Cinema on the Coral Gables campus of the University of Miami for a very limited engagement, until Sunday night. Experimenter has already opened in other cities across the U.S. and is scheduled to open in select cities at later dates. For current playdates, visit this page. It’s also available on demand. All images are courtesy of Magnolia Pictures, who also provided a screener link for the purpose of this review.

We should watch this film to know the behaviors of the past.