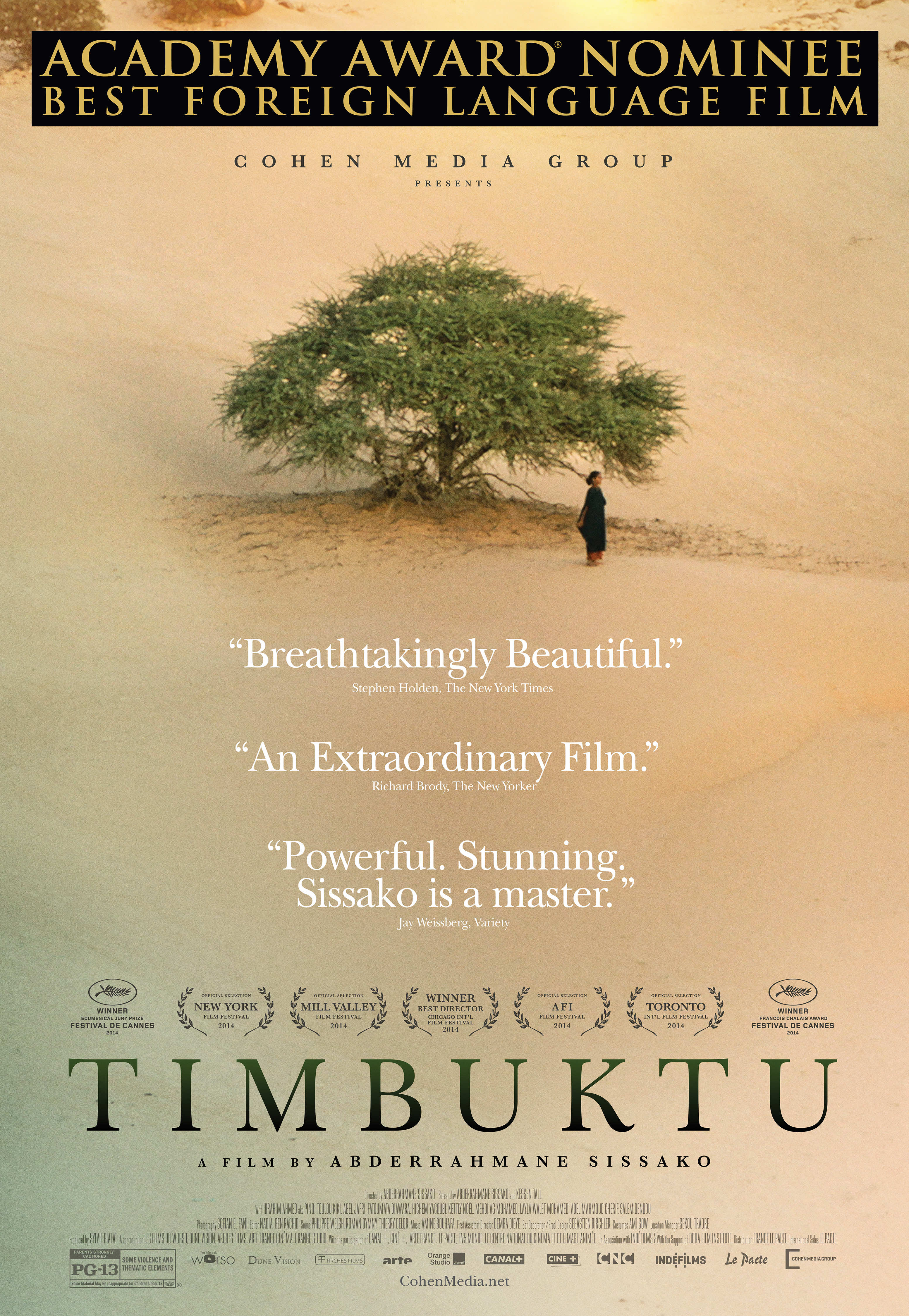

From the country of Mauritania comes Timbuktu, one of the most heart-breaking and humanistic films you will see this year. Do not be turned off if you do not know where Mauritania is, for director Abderrahmane Sissako, who co-wrote the script with Kessen Tall, has put together a border-busting story that is both stark and beautiful. It also helps that the film has been nominated for the best foreign language Oscar. At last year’s Cannes Film Festival, it won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury and the François Chalais Prize.

From the country of Mauritania comes Timbuktu, one of the most heart-breaking and humanistic films you will see this year. Do not be turned off if you do not know where Mauritania is, for director Abderrahmane Sissako, who co-wrote the script with Kessen Tall, has put together a border-busting story that is both stark and beautiful. It also helps that the film has been nominated for the best foreign language Oscar. At last year’s Cannes Film Festival, it won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury and the François Chalais Prize.

Sissako grew up in Mali but was born in Mauritania. As a filmmaker he has worked from Russia and France, making movies concerned with Africa both inside and out. He has not made a movie since his much-loved Bamako (2006), now long out of print on DVD. In interviews, Sissako has said he makes movies when he is called to it. In 2012, the stoning death in a small town in Mali of an unmarried couple who had children outside of wedlock compelled him to make Timbuktu. His extraordinary film tells a story about oppression in Timbuktu by fundamentalist interlopers, true to its current history. Co-produced by a French company, Timbuktu expresses a universal idea informed by the current climate of fear propagated by a fundamentalism that oppresses expression in many forms.

The film opens with a small gazelle running for its life as men, with faces covered by turbans, riding in the beds of speeding pickup trucks displaying a large black flag of Islamic jihad fire AK-47s. Next they are shooting up African masks and statues, including a fertility goddess, symbols of paganism to them but also icons of earthbound humanity. When they arrive at the dusty city if Timbuktu they use a megaphone to announce: “no music, no smoking and women must wear socks.” When they enter a mosque, the imam scolds them, “One cannot enter the house of God with shoes and weapons.”

“But we can. We’re doing jihad,” says one of the men, his mouth covered by a turban. The layers of hypocrisy are rich, from the jihadists’ desire for anonymity to their entitlement, and it permeates this film in various stories featuring an array of characters. Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed dit Pino) lives on the outskirts of the village in a tent with his wife Satima (Toulou Kiki), his young daughter Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed) and Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed), a 12-year-old boy who shepherds Kidane’s small herd of cows. Kidane’s life seems a peaceful one, where he can play guitar and sing to his wife and daughter. Abdelkerim (Abel Jafri) is a jihadist who patrols the outskirts of Timbuktu and has a crush on Satima. He sneaks cigarettes, but as his driver tells him, “Everyone knows you smoke.” Then there’s Zabou (Kettly Noël), a woman who not only does not wear a veil, but wears her unkempt hair and a brightly colored robe with a long train with a pride many dismiss as madness. She is almost Shakespearean in her role as the town fool, having found her own sense of freedom in insanity in this insane world. At least she can get away with calling the jihadists “assholes” and carry on her merry way.

These stories cross only incidentally, and Sissako presents them with little embellishment. Their connections may seem tenuous to some, and there are some characters that are hardly developed and mysteriously drop out of narrative, but it does not detract from the film as much as you might think. It speaks to the chaos and coldness that the jihadists bring to the community. That it does so in such a banal way speaks to the terrible, heavy cloud they have brought to Timbuktu, a once mystical place of romantic mystery.

The film is consistently and impressively shot. There are beautiful wide shots of the arid lands outside the city walls. The vistas are sometimes punctuated by the spare lute and flute-dominant score by composer Amin Bouhafa. But it never comes across as self-conscious and moody. It’s more contemplative, inviting the viewer to appreciate the beauty of a moment of peace. On the other hand, inside the city, dirt streets are crowded by the walls of buildings, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere, and when music appears in the city, it’s in violation of the militants’ law. That some of these men are foreigners adds further insult to their presence for these people who are only trying to live, love and enjoy life in peace, while still recognizing the importance of God in their lives. What becomes terrible is when these people are forced to submit under the threat of sharia punishments like lashings and even execution by stoning. The harsh dualism calls intense attention to the dynamic that drives the film’s drama, and Sissako mostly presents it with a stark, unembellished touch. Violence and even death comes suddenly, interrupting a languorous life defined by the quotidian but peaceful details.

That some of these men are foreigners adds further insult to their presence for these people who are only trying to live, love and enjoy life in peace, while still recognizing the importance of God in their lives. What becomes terrible is when these people are forced to submit under the threat of sharia punishments like lashings and even execution by stoning. The harsh dualism calls intense attention to the dynamic that drives the film’s drama, and Sissako mostly presents it with a stark, unembellished touch. Violence and even death comes suddenly, interrupting a languorous life defined by the quotidian but peaceful details.

What Sissako has created with Timbuktu is a piece of art that reminds the viewer of the everyday beauty of love, be it between people or the arts, like music, and even sports (the film features a surreal and bitter-sweet moment of boys playing soccer without a ball, for even soccer is forbidden by the jihadists). All the while the cloud of terror looms over the drama, driven by an old testament idea of justice and informed by narcissistic, vengeful righteousness, far from anything truly holy. Timbuktu is a vital film presented by a man deeply in touch with his humanity. If it does not call attention to a country cursed by a post-colonialist fate, it should at least speak to the horrors dished out by the more popularly known invaders in Iraq and Syria who are calling for a new nation under the flag of jihad built on the spilled blood of innocents.

Timuktu is in French, Arabic, Bambara and English. It runs 97 minutes and is not rated (some language and stark encounters with violence). It opens Friday, February 5, in the South Florida area at the MDC Tower Theater in Miami and the Cinema Paradiso – Fort Lauderdale. If you live outside of my area, it could be screening in your town already or coming soon. Visit this page (that’s a hot link) for other screening locations across the U.S. Cohen Media provided a screener link for the purpose of this review.

Reblogged this on i-not-chic and commented:

I should watch this!

Thanks for sharing my review. I would love to hear your thoughts after you do watch it.

you’re welcome.

You’re welcome.

Absolutely I will write about my thoughts after I watch it 🙂