Let’s be honest about Winter Sleep, the latest film from Turkey’s premier director/writer Nuri Bilge Ceylan, there is a lot of talking. However, this modern master of highly developed filmmaking also leaves a lot of interesting room for interpretation. Though Ceylan’s films show a specific anxiety for his country, they also reveal a general concern for human relations, be they domestic or social. His films have therefore crossed boundaries and earned praise outside his country (Winter Sleep won last year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes). Though the audience of a Ceylan film should be prepared to invest in what some might consider dense work (this movie is based on the writings of Anton Chekhov), the director makes his work visually inviting, as he has an expressive eye for location, framing of image and a sensitivity for acting. Complicating matters, however, is that his more recent work has meandered at a slower pace, featuring lengthy scenes of dialogue that culminate in extra-long run times. Though this might sound off-putting for the more impatient movie-goer, given a chance, Ceylan’s films can rattle the viewer to the core, as he takes his time to truly explore the complexity of action versus talk, leaving an impact that transcends language.

Let’s be honest about Winter Sleep, the latest film from Turkey’s premier director/writer Nuri Bilge Ceylan, there is a lot of talking. However, this modern master of highly developed filmmaking also leaves a lot of interesting room for interpretation. Though Ceylan’s films show a specific anxiety for his country, they also reveal a general concern for human relations, be they domestic or social. His films have therefore crossed boundaries and earned praise outside his country (Winter Sleep won last year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes). Though the audience of a Ceylan film should be prepared to invest in what some might consider dense work (this movie is based on the writings of Anton Chekhov), the director makes his work visually inviting, as he has an expressive eye for location, framing of image and a sensitivity for acting. Complicating matters, however, is that his more recent work has meandered at a slower pace, featuring lengthy scenes of dialogue that culminate in extra-long run times. Though this might sound off-putting for the more impatient movie-goer, given a chance, Ceylan’s films can rattle the viewer to the core, as he takes his time to truly explore the complexity of action versus talk, leaving an impact that transcends language.

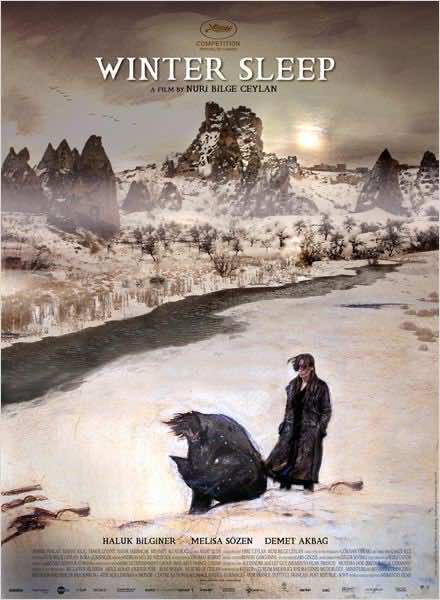

Much of Winter Sleep follows Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a former stage actor now running a hotel named Othello — he has an affection for Shakespeare — in a remote neighborhood of Anatolia, Turkey, that looks as if it had been carved out of the mountains. He lives in the hotel with his divorced sister Necla (Demet Akbag) and his younger wife Nihal (Melisa Sözen). While his manager Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan) collects rent from his downbeat tenants in a nearby village, Ayid prefers to show face to affluent visitors from Japan and other countries. In his dark study, he writes an opinion column for a small community paper. He pontificates on Islam as a religion of high culture. When he gets a letter from a reader stroking is ego and asking for help in building a school for the children in a village, he gives serious thought to taking action.

Aydin translates to “intellectual” in Turkish. Intellectuals are not known for taking action. Thought and writing about thoughts proves to be a perfectly comfortable narcissistic endeavor for this man, and this goes deep. Early in the film, Aydin is called out when a visitor asks about horses on the property, which this visitor had expected based on an image on the hotel’s website. Aydin admits he added the pictures of horses merely for decorative reasons. Feeling a bit guilty, however, Aydin seeks out a horse wrangler, who enlightens Aydin on the costs, time and complexity of capturing a wild horse, especially in winter. Despite the warning, Aydin acts as if money is no object. An allegorical subplot then unfolds that ends with Aydin setting the animal free again.

At the forefront of Aydin’s narrative is the difficult relationships with his wife and sister, just to name two important interactions in the film. They have intense, even epic conversations that build to grand confrontations. Sometimes the arguments go on so long that they seem circular, but they are also building to well-earned, climactic revelations. Nihal is also an intellectual, but she is applying her education and knowledge to political activism with a fellow idealist, which leads to some petty jealousy from Aydin. She wants to take action and actually do good for those in need, and she earns every right to complain about her husband’s “unbearable inconsistency” to criticize people for either being religious or not, only if it benefits his argument.

Meanwhile, Aydin’s unwritten book on a history of Turkish theater looms over their ever-corroding marital malaise. His solution is to give her money and entrust her to make a donation of it. Indeed, it will be she who will try to make good of this gesture, but Nihal is no flawless do-gooder either. Ceylan is much too subtle to allow her gesture to ring hollow. She does something with the money blinded by idealism, and she’s in for a harsh lesson right out of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. It’s all well and good to give away money to those in need but not so easy to fix things with a gesture as simple as that.

This is barely the surface of what happens in Winter Sleep. There is an attempt at spiritual enlightenment fueled by damaged ego and alcohol, and many of the confrontations reveal a concern for patriarchal righteousness. Ceylan deals with complex interactions of ideals, human nature and behavior and their consequences. Various characters tangle with pride, from both a very young and naïve perspective or an embittered, older perspective. A character some might overlook is Hamdi hodja (Serhat Mustafa Kiliç), the brother of one of Aydin’s tenants, Ismail (Nejat Isler) an alcoholic father with a dark, complicated past that is not revealed until near the film’s end. As an imam, Hamdi is more devout than Aydin. He also has a more genuine desire to make things right, but he also curses those he considers oppressors under his breath. The performances are amazing and appropriately dynamic throughout the film. The dialogue, though in a foreign language to this writer, feels natural, full of concern for understanding, as if these characters are indeed listening to one another and reacting, often to heartrending effect.

The complex, interesting characters populate a rather sublime backdrop captured in engrossing, panoramic anamorphic shots. The locations are often an expressive brown, gray and white, sometimes a very brilliant white with hints of blue. It’s a physical manifestation of the “gray area” at the heart of the film. Though it is dialogue that makes most of the film’s soundtrack, Winter Sleep also features an appropriately moody recurring musical theme in Schubert’s “Sonata No. 20 in A Major,” a melody that some might recognize from Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar.

Over the course of nearly 20 years, Ceylan’s film style has evolved in such interesting ways. Though I admired the effort of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia to offer a byzantine array of perspectives (sometimes within the same person) in the face of a murder mystery, it felt rather grueling. The lack of connection between the characters had a chilling effect early in the film. Winter Sleep is a much stronger work, however. While exploring varied perspectives between the characters, Ceylan weaves profound connections between them that make for an intensely moving film. It may feel long and drag a bit in the middle, especially when Aydin and Nihal take a painful mental journey into where they stand in their long marriage, but there’s a precious reward to be had when it all comes together at the end. It arrives not so much with a neat bow of clear conclusion but a deepening of insight into human connections and perspectives.

Too often, especially in escapist-driven Hollywood, films effectively numb us to consequences. Violence and abuse is heightened with humor, music and editing. We are rewarded with Schadenfreude and exit the theater with a dismissive feeling of contentedness that the mirror of the movie screen did not reflect us. Ceylan’s work is important in that it makes viewers aware of the consequence of actions driven by righteousness that affect those around us with a delicate, engrossing style stripped of gimmick and full of genuine concern and thought. It shows us the importance of empathy with patience and a generosity in storytelling and visuals that never feel condescending or preachy, just very raw and real.

Winter Sleep runs 196 minutes, is in Turkish and English with English subtitles and is not rated (it has some domestic violence [mostly emotional] and maybe some language, but it should not be offensive to most, except maybe the impatient). It opens Friday, Jan. 9, in South Florida. It plays in the Miami-Dade area at the Miami Beach Cinematheque, which invited me to a preview screening for the purpose of this review. In Broward it will show at the Cinema Paradiso – Fort Lauderdale and the Cinema Paradiso – Hollywood. If you live outside of South Florida, it may already be playing in your neighborhood or coming soon. Visit the film’s website and click “view theaters and showtimes” for U.S. screening info.

This looks well worth checking out. Enjoyed “Uzak” but have not seen any of his other films.

Yes, Rick! I can imagine you will like this one too.