It’s not always another person that can get between two lovers. In his first English-language film, Norwegian director Erik Poppe finds inspiration by looking to his own experiences and the dissolution of his marriage during a time when he was a war photographer. With 1,000 Times Good Night he presents a woman who is so caught up in her work she will risk not only her life, but her place as a mother to follow her ideology. There’s an empowerment of gender in his choice to explore his story through a woman’s perspective, but it also never softens the sacrifice involved, and Poppe delivers the point in a nerve-racking opening scene with hardly any dialogue, as a good photographer-turned-filmmaker would.

It’s not always another person that can get between two lovers. In his first English-language film, Norwegian director Erik Poppe finds inspiration by looking to his own experiences and the dissolution of his marriage during a time when he was a war photographer. With 1,000 Times Good Night he presents a woman who is so caught up in her work she will risk not only her life, but her place as a mother to follow her ideology. There’s an empowerment of gender in his choice to explore his story through a woman’s perspective, but it also never softens the sacrifice involved, and Poppe delivers the point in a nerve-racking opening scene with hardly any dialogue, as a good photographer-turned-filmmaker would.

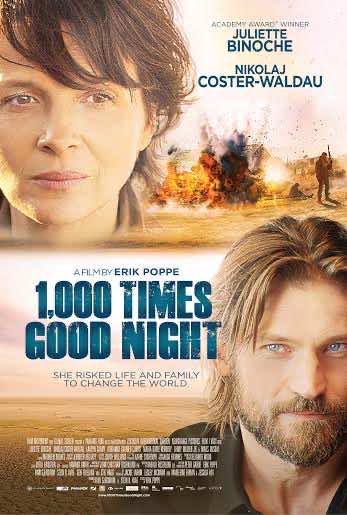

Juliette Binoche plays Rebecca, who has somehow found a way to photograph the ritual of a female suicide bomber as she heads out to detonate herself. The film’s title alludes to the explosive-laden vest and the ritual, but also reflects on Rebecca’s personal notion of martyrdom for her own ideology, though she prefers not to recognize it. When her zeal to get as close to the explosion as possible starts to clash with her conscience, she inevitably gets hurt. Though she survives, physical wounds reverberate to emotional difficulties that affect her entire family, which includes two daughters — one a child, the other a teenager — and a husband, played by Nikolaj Coster-Waldau.

The film plays with the dynamic between husband and wife as if another lover has come between them. After Rebecca’s husband Marcus takes her home from the hospital, there’s a tension of something profoundly unmentionable between them. The two are almost on entirely different wavelengths about what has happened, and they dare not speak about it. That the movie shows this with hardly any dialogue, speaks to the performances and Poppe’s eye for showing a story rather than relying on heavy-handed exposition.

The film takes its time to follow a neat story arc that ends with a significant pay-off that will hopefully lead to some growth for this woman, but it will not come without sacrifice. These people have issues, and they keep them inside for some time. The film appropriately has to spend some time in tense silence for much of the early part of the film so that it might allow the audience to appreciate and contemplate a genuine tension between the couple. It will then earn the confrontation between the two when one of them finally finds the courage to say something about the ever-widening gulf between them.

Coster-Waldau and Binoche rivet the film with strong performances. The actors deliver in both silence and the inevitable explosion of their repressed feelings. When Marcus confronts Rebecca about how her work has detrimental effects on the family, Binoche transmits the pain and shame of having been trapped between her family and a passion for her work as if she had been caught in an infidelity. It’s a brilliant moment that reveals the silent precision of Binoche’s acting chops. Throughout the movie, Binoche never seems lost in some haze of ambiguity. This is a woman of convictions, and she carries that burden heavily.

The film has a conscience, but it also explores the flip side, which is the pain of sacrifice one makes for ideals, and it’s complex impact on loved ones. There’s a moment when Rebecca schools her elder daughter Steph (Lauryn Canny) on the problems in Africa, the role of corporations in those problems, including a lack of human rights and the news business’ interest in celebrity photographs over her war journalism. Steph has an admiration for her mother informed by her love for not only a mother but also a hero standing up for human rights. But that love will be put to the test at a refugee camp in Kenya, which a colleague tells Rebecca is completely safe for her to bring her daughter to.

This refugee camp is the site of another intense sequence of danger when marauding rebels come in with AK-47s blasting. Rebecca cannot seem to contain her impulsiveness to get shots of the conflict, despite leaving her tearful daughter to enter the melee. It might seem illogical for a parent to do that, but Binoche is so good at capturing the passion of this woman she genuinely sells her as someone who can hardly control her addiction to adrenaline. It almost seems like a reflex for the woman, as not even the worried tears of her daughter can sway her from her job.

The film could have easily drowned itself in over-the-top melodrama, but it never does thanks to the carefully modulated acting of Binoche and the patient, deliberate construction of the story by Poppe and his co-writers. 1,000 Times Good Night does not glamorize the photographer. It presents her as a torn person who never seems whole without her camera and conflict but still understands her place as a mother. Poppe’s personal experience informs this complex character profoundly, and because he once was that person, he understands an end point will come. Whether a family can survive this force in their life is never fully resolved, but he builds toward a finale that shows there may be a wake-up call coming for this woman, and it relies on much of the film’s painstakingly constructed drama.

Note: Read my interview with Coster-Waldau on this movie, working with Binoche and his personal investment in his character here:

Nikolaj Coster-Waldau talks about bringing personal experience to his role in ‘1,000 Times Good Night’

1,000 Times Good Night runs 117 minutes and is not rated (contains violence and language). It opened in South Florida this past Friday at the Bill Cosford Cinema in Coral Gables and the Tower Theater in Miami. It’s opening across the U.S. right now. To see other play dates across the nation, visit this link. Film Movement provided a screener link for the purpose of this review.