The notion of love is a slippery thing, and the Deep Blue Sea, captures its elusive sensation with a visual patchwork of evocative and dramatic scenes that forgoes exaggerated set-ups like fancy weddings and over-the-top situations. Too often Hollywood celebrates contrived situations like the Vow* to conveniently tell a story of people in love. How about something more expressive, abstract and complex, like the sublime experience itself? Director Terence Davies subverts traditional storytelling with his latest and captures not just people in love, but people who love but never click. I’ll go out on a limb and say no one has done this better since Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood For Love. By defying a straight forward narrative and working in expressive, almost photographic collage, Davies recreates something more beholden to a feeling than most films with lovers at its center.

The notion of love is a slippery thing, and the Deep Blue Sea, captures its elusive sensation with a visual patchwork of evocative and dramatic scenes that forgoes exaggerated set-ups like fancy weddings and over-the-top situations. Too often Hollywood celebrates contrived situations like the Vow* to conveniently tell a story of people in love. How about something more expressive, abstract and complex, like the sublime experience itself? Director Terence Davies subverts traditional storytelling with his latest and captures not just people in love, but people who love but never click. I’ll go out on a limb and say no one has done this better since Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood For Love. By defying a straight forward narrative and working in expressive, almost photographic collage, Davies recreates something more beholden to a feeling than most films with lovers at its center.

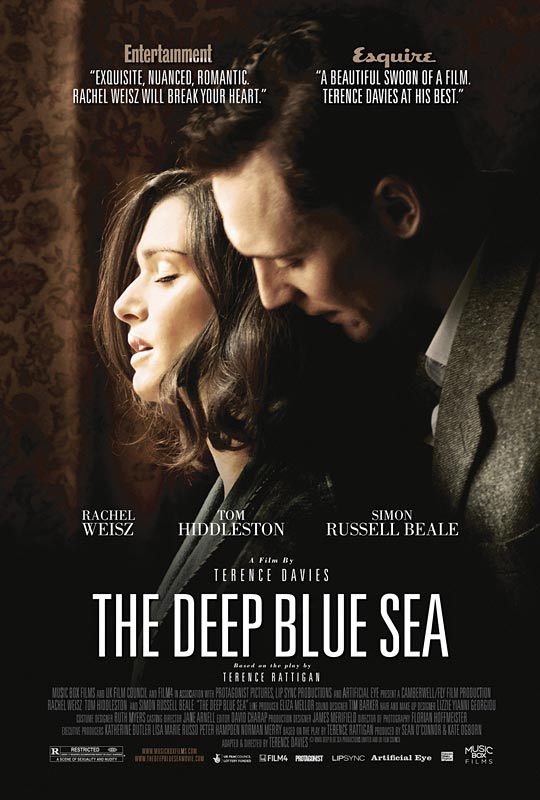

We meet Hester (Rachel Weisz) at the height of her most passionate moment in love. She is about to kill herself. The viewer has to work to put the pieces together, as the situation leading up to this moment unfolds in a patchwork of flashbacks.  In fact, a second viewing of the Deep Blue Sea will probably prove more satisfying than the first. Though the film has its dramatic moments, Davies’ loose, flowing work captures experience in retrospect, similar to our own recollection of jumbled memories. In effect, offering a more human connection to the audience better than a straight-up narrative would ever achieve.

In fact, a second viewing of the Deep Blue Sea will probably prove more satisfying than the first. Though the film has its dramatic moments, Davies’ loose, flowing work captures experience in retrospect, similar to our own recollection of jumbled memories. In effect, offering a more human connection to the audience better than a straight-up narrative would ever achieve.

The film opens with pure evocation. A simple blue light spreading over a dark screen, as if coming up from the dark depths of the ocean. As the credits unfold in simple, swelling white block letters, the blue light gradually emerges** Davies seems to be offering the abstract representation of love entering one’s life. It’s a minimalist version of how the world seems to feel a little brighter, more Technicolor, when a new love appears. Opening credits do matter (see yesterday’s review), and not enough filmmakers use them nowadays.

When the neighborhood Hester lives in fades in from the darkness of this opening sequence, it almost appears alien. A series of streaming lights from a tangle of weeds seem so unreal it may as well be fairies dancing out of the dark. As the filtered camera lens lethargically pans left, the title card “LONDON” appears, followed by “AROUND 1950,” as it becomes apparent that this is a late-night suburban street scene.  The camera continues its sluggish movement into a window where Hester stands. There is a blue and gold tint to everything, giving the interior of Hester’s apartment an unreal glow. The camera does not follow her as she goes through the motions of preparing for her own demise. She closes the curtains, fade. She bolts the door, fade. She puts a towel at the bottom of the door, fade. And so forth. These are key moments, as if recalled, whatever footsteps in between forgotten to lost, superfluous time. Before she lies down, a diamond-shaped mirror with roses intricately painted on its surface catches her face. The reflection stands out among the busy detritus that fills the apartment. Already the consistently beautiful shots recall a sense of In the Mood For Love. Whoever is playing a violin during the accompanying score (Samuel Barber’s “Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 14”) is not holding back, as the stringed instrument seems to scream and howl after Hester turns on the gas, and the film fades to another time and another place.

The camera continues its sluggish movement into a window where Hester stands. There is a blue and gold tint to everything, giving the interior of Hester’s apartment an unreal glow. The camera does not follow her as she goes through the motions of preparing for her own demise. She closes the curtains, fade. She bolts the door, fade. She puts a towel at the bottom of the door, fade. And so forth. These are key moments, as if recalled, whatever footsteps in between forgotten to lost, superfluous time. Before she lies down, a diamond-shaped mirror with roses intricately painted on its surface catches her face. The reflection stands out among the busy detritus that fills the apartment. Already the consistently beautiful shots recall a sense of In the Mood For Love. Whoever is playing a violin during the accompanying score (Samuel Barber’s “Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 14”) is not holding back, as the stringed instrument seems to scream and howl after Hester turns on the gas, and the film fades to another time and another place.

Following another fade out, the tone of the images grow more subdued and flat, dominated by the plainness of brown and darkness. We see Hester again, dressed differently, sitting in a plush chair inside a study, half-smiling to her husband William (Simon Russell Beale), who sits behind a desk. When he is not looking, she tears up. We know she is not thinking of him during this attempt on her life. Fade. Hester is sitting outdoors on a patio bench, on a bright, sunny day. Everything shimmers in soft focus, and the scene seems dominated by an incandescent white. A debonair looking man, Freddie (Tom Hiddleston, who recalls Michael Fassbender) smiles at her. We will later learn he becomes the man who has taken her heart.

When he is not looking, she tears up. We know she is not thinking of him during this attempt on her life. Fade. Hester is sitting outdoors on a patio bench, on a bright, sunny day. Everything shimmers in soft focus, and the scene seems dominated by an incandescent white. A debonair looking man, Freddie (Tom Hiddleston, who recalls Michael Fassbender) smiles at her. We will later learn he becomes the man who has taken her heart.

More scenes unfold, jumping here and there through time and space. The link between them is a magnetism between the people or a pushing away. There are efficient moments of dialogue with little context. What provides more information comes from Davies’ visual prowess: the framed shots of Hester and Freddie, smiling at each other. He chatting close to her face, and she taking it in.  Meanwhile, William and Hester walk separate ways and are never shot without something between them. The best obstacle being William’s mother (Barbara Jefford bringing on the mean old lady). On one of the few occasions the husband and wife face each other, it’s at a dinner table with the mother passive-aggressively offering such tidbits like “Beware of passion, Hester. It always leads to something ugly … A guarded enthusiasm is much safer.”

Meanwhile, William and Hester walk separate ways and are never shot without something between them. The best obstacle being William’s mother (Barbara Jefford bringing on the mean old lady). On one of the few occasions the husband and wife face each other, it’s at a dinner table with the mother passive-aggressively offering such tidbits like “Beware of passion, Hester. It always leads to something ugly … A guarded enthusiasm is much safer.”

But would the film be more interesting taking a safe path? In the end, lust does die out, and Freddie becomes more than the cypher that wedged itself between the married couple. He is the product of war, a topic often explored by Davies. When we meet him early on, he talks of the “excitement and fear” of battle. “There is nothing like it,” he says. He will never find that kind of passion in this downtrodden wife, and the broken triangle, elegantly but tragically creeks forward.  Mirrors often appear in the movie, a nice cinematic touch referring to false perceptions, and as the knots tangle and ultimately break, Davies dives in with unrelentingly gorgeous takes. The actors are captured at their most passionate moments. It’s not what they do, but how they do it. That simple early shot of Weisz in the study, turning a delicate, forced smile to quiet tears captures the profound sadness that is this tragic story.

Mirrors often appear in the movie, a nice cinematic touch referring to false perceptions, and as the knots tangle and ultimately break, Davies dives in with unrelentingly gorgeous takes. The actors are captured at their most passionate moments. It’s not what they do, but how they do it. That simple early shot of Weisz in the study, turning a delicate, forced smile to quiet tears captures the profound sadness that is this tragic story.

The Deep Blue Sea is not a fun film, but it is an honest one… and beautifully shot. Davies, who happens to be a gay man raised in 1950s post-war England, captures not only this difficult form of love expertly but also the era. Love is a powerful feeling and few films can capture that power as well as this movie. Too often writers have to cook up stories that falsely try to represent the feeling. It’s a sublime experience that demands a sublime touch, you’ll find that in the Deep Blue Sea.

Trailer:

*Yes, I know the Vow is based on a true story, but leave it to Hollywood to adapt it into a movie. Plug in While You Were Sleeping, Serendipity or even the Twilight movies, whatever such dreck you like. It’s all the same.

The Deep Blue Sea is rated R, runs 98 min. It plays opens in South Florida Friday, Mar. 23 at an array of theaters, including:

Miami: Miami Beach Cinematheque, UM’s Bill Cosford Cinema, AMC Aventura 24, AMC Sunset Place

Fort Lauderdale: The Classic Gateway Theatre, Boca Raton: Living Room Theaters, Regal Shadowood 16

Delray Beach: Movies of Delray, Regal Delray Lake Worth: Movies of Lake Worth, Jupiter: Cobb Jupiter 18

If you are outside South Florida, the film’s national screening dates can be found here.

(Copyright 2012 by Hans Morgenstern. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.)